Explore the Fascinating History of Petra, a Once-Lost City That’s Now a Wonder of the World

Photo: Stock Photos from jaras72/Shutterstock

Also known as the Rose City, the prehistoric city of Petra is an incredible spectacle that one must see to believe. The once-thriving trade center was settled in the 4th century BCE. Its architecture, which is carved into the red sandstone cliffs, has helped make it one of the New 7 Wonders of the World. Located in the desert canyons of southwestern Jordan, Petra was the capital of the ancient Nabataean civilization.

Stretching over 102 square miles, Petra is an incredible site that attracted over one million tourists in 2019. Astoundingly, what we see today is just a fraction of what the ancient city has to offer. Archeologists have only excavated 15% of the site, so an amazing 85% of it is still buried underground.

For those who have never visited, you may still be familiar with Petra thanks to its role on the silver screen. Films like Indiana Jones and the Last Crusade, The Mummy Returns, and Aladin have all used its unique archeology as a backdrop.

Photo: Stock Photos from Usoltceva Anastasiia/Shutterstock

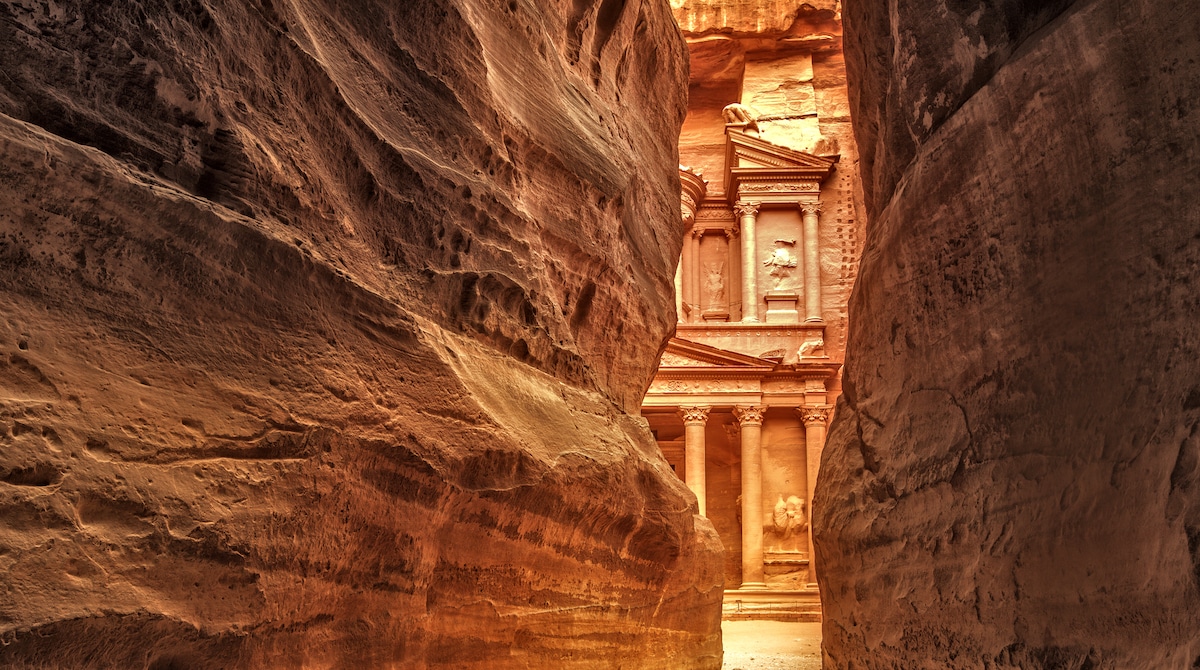

Today, when people approach the site, they'll find themselves following the same path that traders and visitors have been using since Petra was created. A long, curving gorge known as the Siq is a prelude to what awaits. Literally translating to “the shaft,” the three-quarters of a mile long trek builds anticipation for what lies ahead. Decorations that include a carved camel and niches that would have held Baetylus—sculptural embodiments of gods—adorn the path.

Though it may seem like a long walk to get to the main action, it's well worth soaking in the moment. Soon enough, the first glimpse of Petra's famous architecture will appear.

The Nabataeans

Photo: Stock Photos from tenkl/Shutterstock

The Nabataeans were a nomadic Bedouin tribe that traversed the Arabian desert and created Petra. They emerged as a political power between the 2nd and 4th centuries BCE and set about building their capital, which we now call Petra. However, this was not the city's original name, as the Nabataeans referred to it as Raqmu.

Nabataean culture gained wealth and stability thanks to its control over a trading network that was critical to the ancient world. Because of their involvement in trade, they were exposed to and influenced by different cultures from the Mediterranean and Arab world. These influences were incorporated into their religion and culture.

Petra is an incredible expression of their wealth and power. At one time, it was home to 30,000 people. Thanks to its strategic location, it was a difficult city to conquer, and later, when the Nabataeans were overcome by the Romans, it only continued to expand. In fact, it's possible to see the influence of Roman architecture throughout Petra.

The Nabataean kingdom continued to thrive for several centuries after it was annexed into the Roman kingdom in 106 CE. But eventually, for reasons that aren't quite clear, they fell into squalor and their land was divided up among different Arab kingdoms.

The Rediscovery of Petra

Photo: Stock Photos from klempa/Shutterstock

Petra was largely abandoned after the 8th century CE. Though nomadic shepherds continued to use the structures for shelter, it stayed unknown to the Western world for over a thousand years. That all changed in the 19th century when Swiss explorer Johann Ludwig Burckhardt “discovered” the ruins.

Burckhardt was traveling to Syria to improve his Arabic when he heard the story of a German explorer who had been murdered while searching for the lost city of Petra. Determined to find it, Burckhardt used the name Sheikh Ibrahim Ibn Abdallah to hide his identity and went about embedding himself into society. After several years in Aleppo, he felt confident enough to make the journey to Cairo and hopefully pass by the ruins.

It was while traveling inland in Jordan on the way to Aqaba that he heard rumors about ancient ruins nearby. As this coincided with what he'd heard previously about Petra, he pretended that he wanted to sacrifice his goat and asked his local guide to take him to the tombs to do so. It was at this point that he was led through the Siq and, in 1812, became the first Westerner to view Petra.

Photo: Stock Photos from Firebird007/Shutterstock

“An excavated mausoleum came in view, the situation and beauty of which are calculated to make an extraordinary impression upon the traveler, after having traversed for nearly half an hour such a gloomy and almost subterraneous passage as I have described,” he wrote in a book recalling his travels. “In comparing the testimonies of the authors cited in Reland's Palastina, it appears very probable that the ruins in Wady Mousa are those of the ancient Petra, and it is remarkable that Eusebius says the tomb of Aaron was shewn near Petra. Of this at least I am persuaded, from all the information I procured, that there is no other ruin between the extremities of the Dead Sea and the Red Sea, of sufficient importance to answer to that city.”

After Burckhardt's amazing discovery, many Western explorers came to Petra to make drawings of the structures and study its architecture. This paved the way for its beauty to be known across the globe.

Al Khazneh

Photo: Stock Photos from Richie Chan/Shutterstock

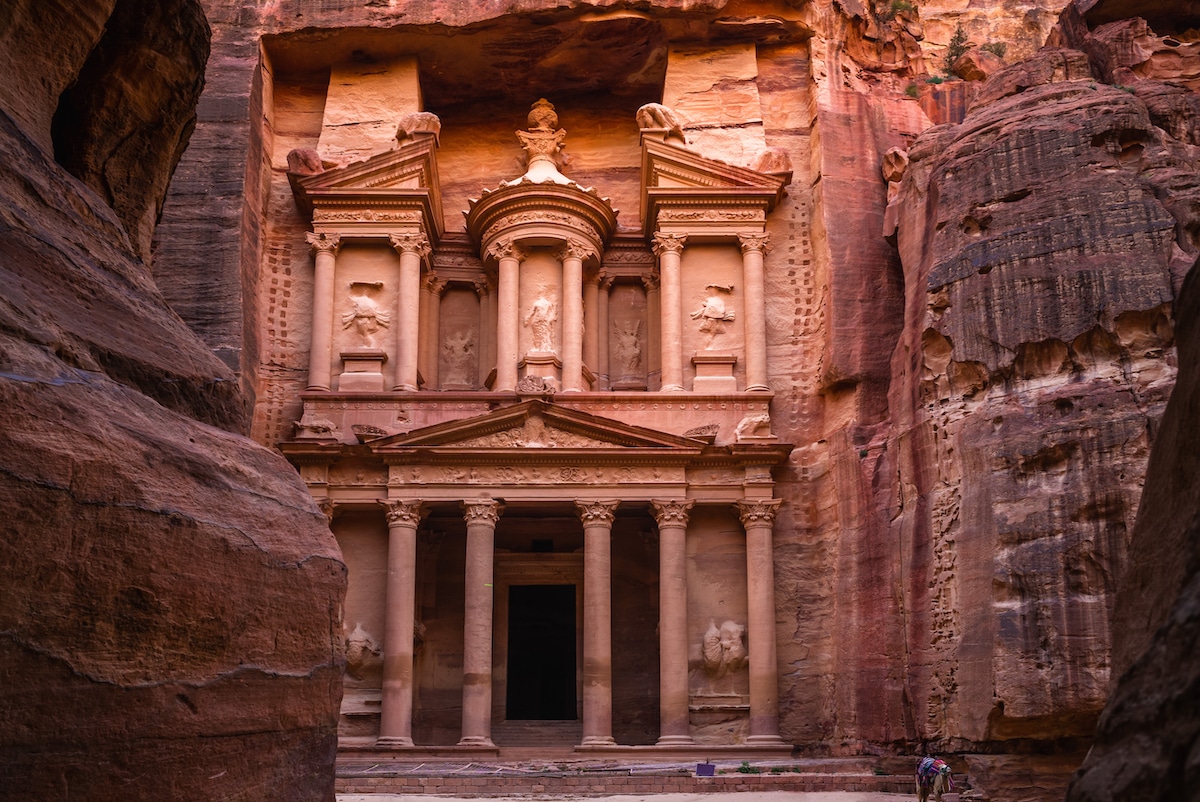

One of Petra's most iconic structures is Al Khazneh, the Treasury. Carved into the face of red sandstone rock, it rises up 127 feet high and is nearly 82 feet wide. It stands at the most important entry into Petra from the Siq, and its importance is underscored by its elaborate decoration. Almost Hellenistic in style, it's adorned with floral and figurative decoration as well as architectural elements like columns and pediments that recall ancient Greek temples.

Though it's called the Treasury, the structure is actually a tomb. Given its prominent location, archaeologists are almost certain that it was the tomb for a Nabataean king or queen. Unfortunately, as no coins or pottery have been found that could help unravel the mystery, we still don't know the exact date of its creation or for whom it was created. However, King Aretas IV, who ruled between 9 BCE and 40 CE, is a likely candidate. As the Nabataean's most successful ruler, he led at a time when Petra was at its peak and many of its buildings were constructed.

Photo: Stock Photos from Aleksandra H. Kossowska/Shutterstock

So if Al Khazneh is a tomb, why do people call it the Treasury? This stems from the early 20th century when Bedouins became convinced that the urn on the second story contained the treasure of an Egyptian Pharoah. In fact, they were so sure that they continuously shot at it hoping to release the treasure. After that, the name stuck. Appropriately, in Indiana Jones and the Last Crusade, Al Khazneh is used as the location of the Holy Grail—one of the world's ultimate treasures.

Today, millions flock to drink in the majestic architecture of Petra and marvel at the prehistoric society that left behind such a big impression.

Photo: Stock Photos from Truba7113/Shutterstock

Photo: Stock Photos from Ronsmith/Shutterstock

Photo: Stock Photos from upslim/Shutterstock