During its first half-century, the relationship between the cinema and the novelist has been marked by unmistakable qualities of envy, of acerbity, of persistent, uneasy tension. The industry, with the swaggering assurance of the nouveau-riche, pays handsomely for talent or material which it has scarcely troubled to learn how to use. Aldous Huxley is set to work on Pride and Prejudice, Faulkner to cut Hemingway to the pattern of a wartime novelette; Hecht adapts Wuthering Heights and Isherwood makes an Ava Gardner vehicle out of Dostoievsky. Writers see their own work mutilated to meet box-office fashions or censorship taboos.

Literary critics – like drama critics, who tend to survey the stage appearances of film stars with the weary condescension previously reserved for performing animals – treat the cinema as a road to damnation. Novelists who have been press-ganged into the alien service take their money and leave, sometimes to avenge themselves with pictures of a Hollywood matching Renaissance opulence with a Borgia talent for intrigue and deception .

At bottom, perhaps, the problem is more serious: Scott Fitzgerald wrote in The Crack-Up:

“I saw that the novel, which at my maturity was the strongest and supplest medium for conveying thought and emotion from one human being to another, was becoming subordinated to a mechanical and communal art that, whether in the hands of Hollywood merchants or Russian idealists, was capable of reflecting only the tritest thought, the most obvious emotion. It was an art in which words were subordinated to images, where personality was worn down to the inevitable low gear of collaboration.

”As long past as 1930, I had a hunch that the talkies would make even the best-selling novelist as archaic as silent pictures… there was a rankling indignity… in seeing the power of the written word subordinated to another power, a more glittering, a grosser power. The advance of the communal art may be inevitable; it is also as alarming as any revolutionary process, and the novelist may choose to see himself as the last defendant of the old order. Yet the attraction of the industry is not only in the price it pays: power itself fascinates.”

Scott Fitzgerald’s own career shows the interaction with the cinema that has become almost a pattern for the successful novelist. Hollywood bought his works, and did its worst with them. Fitzgerald made two abortive visits as a scriptwriter and then, at the time when his popular reputation was at its lowest, when the critics had attacked Tender is the Night and he had documented the history of his own collapse in The Crack-Up, he went to Hollywood again. His unfinished novel, The Last Tycoon, may be taken to sum up what he felt: the old, powerful fascination of the medium, the disillusioning experience of strategy and compromise, the sense of waste and corruption and of vast, partly realised possibilities. In a nation that “for a decade had wanted only to be entertained” the pull of Hollywood, however it might deflect a writer from his true course, was not to be resisted.

Gatsby in Hollywood

ln the early 20s Scott Fitzgerald, on the strength of a single adolescent novel which seemed to catch the mood of a generation, achieved that fantastic, irrational popular success typical of a decade of wild enthusiasms. His short stories were bought, inevitably, by the plot-hungry cinema – three were filmed between 1920 and 1922. His second novel, The Beautiful and Damned, was filmed by Warners in the year of publication, with Marie Prevost and Kenneth Harlan as the ill-fated, if scarcely tragic, Gloria and Anthony. Photoplay commented:

“If he depicts life as a series of petting parties, cocktails, mad dancing and liquor on the hip it is because he sees our youthful generation in these terms… it is our youthful fascisti possessing the measure of money and knowledge, fighting against the swing of the pendulum which has brought us the you-must-not era.”

Fitzgerald, in Echoes of the Jazz Age, said of the films of the 20s:

“The social attitude of the producers was timid, behind the times and banal- for example, no picture mirrored even faintly the younger generation until 1923… there were a few feeble splutters and then Clara Bow in Flaming Youth; promptly the Hollywood hacks ran the theme into its cinematographic grave.”

The screen versions of his own stories were probably among the more feeble of the splutters.

The Great Gatsby was first produced by Paramount in 1926, directed by Herbert Brenon, with Lois Wilson as Paisy, Warner Baxter as Gatsby, Neil Hamilton as Tom Buchanan and William Powell as Wilson. The general tone of the film may perhaps be imagined from comments in the trade press; there was some disapproval of a scene showing Daisy drunk on her wedding day, and the Kinematograph Weekly complained that “all the characters are morally unsound”. It summed up the plot as a story of “How one man’s failure brought happiness to two others” – Tom and Daisy, in other words, came out all right.

After this, the cinema ignored Fitzgerald for more than 20 years: M.G.M. acquired the rights of Tender is the Night, but after Irving Thalberg’s death Fitzgerald wrote to a friend “I think that he killed the idea of either (Miriam) Hopkins or Fredric March doing” the novel. As late as 1949, however, perhaps because of the fashion for screen psychiatry, M.G.M. were dickering with the idea of filming this fascinating but, one feels, almost untranslatable book. The title appeared in a production schedule, and that was all.

In the same year Paramount resurrected Gatsby, directed by Elliott Nugent from a script by Richard Maibaum and Cyril Hume (the latter a Tarzan screen writer, among other credits). This was the occasion for a quite remarkable accumulation of imaginative disasters, of which the most striking was the casting of Alan Ladd as Jay Gatsby. The essence of Gatsby is his capacity for wonder, his overpowering imaginative audacity in the service of “a vast, vulgar and meretricious beauty”; the incorruptible dream, expressed in make-believe luxury and built on a lurid foundation of corruption, points the contrast to the alluring, shallow, vicious world of the Buchanans. The screen’s favourite impassive gunman could be expected to suggest nothing of this. Betty Field, more subtly miscast, played Daisy with sensitivity but a somehow rather too consciously worked out sense of the period; Barry Sullivan was an anonymous Buchanan; Macdonald Carey a half-hearted Nick Carraway, and Shelley Winters a too strident Myrtle Wilson.

But the film, with its March of Time style introduction to the 20s, with flashbacks breaking up the whole balance and compression of the novel, missed all its chances. Even the visual symbols – Gatsby’s disorganised, dream-like parties in his Xanadu fantasy of a palace, the waste land round Wilson’s garage, the sticky summer heat in the New York apartments, the green light shining from the Buchanan’s dock – were fumbled and lost. The tone, although rather truer to the original than one imagines the 1926 version to have been, was weakened by a final orgy of repentance; Daisy repents and tries to warn Gatsby; Jordan Baker, whose activities have been extended from cheating in a golf match to chiselling a car out of Gatsby, repents; unforgiveable, Gatsby repents. His last speech strings together the tired cliches of the gangster hero: he is going to “take this rap for the sake of boys like Jimmy Gatz” – so much for the incorruptible dream.

In spite of everything, the film had that curious air of flawed distinction, apparent in the occasional attitude to a character, in stray lines of dialogue (not Gatsby’s famous “her voice is full of money” which, typically, was omitted) that identify the source however faltering the adaptation. Paramount shot their bolt too soon. They are not likely to film Fitzgerald’s wonderfully sharp, controlled, evocative novel again for some time, but, after A Place in the Sun, one feels that in George Stevens they might have the director to do it.

“A crowd of fakes and hacks”

Scott Fitzgerald’s own Hollywood career began in 1927, when he went out under contract to United Artists to do “a fine modern college story” for Constance Talmadge. The result, Lipstick, was never made; Arthur Mizener, in The Far Side of Paradise, calls it “a competently plotted if conventional story about a girl at a prom”. Later, with his characteristic mixture of apparent naive conceit and disconcerting self-knowledge, Fitzgerald wrote:

“I had been generally acknowledged for several years as the top American writer both seriously and, as far as prices went, popularly… I honestly believed that with no effort on my part I was a sort of magician with words… Total result – a great time and no work. I was to be paid only a small amount unless they made my picture – they didn’t.”

In 1931 he did some work for M.G.M. on a film called Red Headed Woman; this was made, with Jean Harlow, Chester Morris and Charles Boyer; the script credit went to Anita Loos. Fitzgerald had worked under difficulties and was dissatisfied. “I left with the money but disillusioned and disgusted, vowing never to go back, tho’ they said it wasn’t my fault and asked me to stay.”

He did go back however, in 1937. It may be taken as almost axiomatic that the cinema does not attract a novelist at the height of his powers (there is a revealing little scene in The Last Tycoon when Stahr explains, “we don’t have good writers out here… we hire them, but when they get out here they’re not good writers”) and Fitzgerald in 1937 was in debt, out of fashion, and worn out. At the same time his hopes, as usual, were high, and were characteristically expressed in a letter to his daughter:

“The third Hollywood venture. Two failures behind me though one no fault of mine… I want to profit by these two experiences! must be very tactful, but keep my hand on the wheel from the start – find out the key man among the bosses and the most malleable among the collaborators – then fight the rest tooth and nail until, in fact or in effect, I’m alone on the picture. That’s the only way I can do my best work. Given a break I can make them double this contract in two years.”

But a little later he said of Hollywood:

“A strange conglomeration of a few excellent, over-tired men making the pictures and as dismal a crowd of fakes and hacks at the bottom as you can imagine.”

In any case, if the journey to Hollywood was a retreat, it was a determined, combative retreat. Fitzgerald’s first and last screen credit was for Three Comrades, made by M.G.M. (to whom he was under contract) and directed by Frank Borzage. This was the sort of high-class tear-jerker, as artificial in its own way as the crazy comedies, that almost died out with the 30s: social significance has partly replaced the luxury of manufactured emotion. The Comrades, three young German soldiers in the first war, go into the garage business together; one (Robert Young) engages in some rather vague political activity and is killed; another (Robert Taylor) falls in love with a tubercular girl (Margaret Sullavan, adept in wistful pathos), who dies as slowly and as theatrically as Camille.

It is peculiarly difficult to apportion credit for this script: there is the novel, there is the co-script writer, Edward Paramore, an old hand, and there is the producer, Joseph Mankiewicz. Fitzgerald wrote bitterly to him:

“To say I’m disillusioned is putting it mildly. I had an entirely different conception of you. For 19 years… I’ve written best selling entertainment and my dialogue is supposedly right up at the top. But I learn from the script that you’ve suddenly decided that it isn’t good dialogue and you can take a few hours off and do much better… Oh, Joe, can’t producers ever be wrong? I’m a good writer – honest. I thought you were going to play fair.”

The emphasis on “best selling” is a part of Fitzgerald’s oddly divided attitude to his own work. But one wonders how many letters like this have been written during Hollywood’s first 40 years.

If it is impossible to guess how much of Fitzgerald the film holds, at least the temper and mood are not altogether alien to him. The doomed heroine, sentimentalised though she is, seems a blurred version of a Fitzgerald girl; the note of controlled, compassionate despair appears at moments almost incongruously authentic.

After this, Fitzgerald never again achieved that sine qua non, a screen credit. M.G.M. employed him on a Joan Crawford picture, Infidelity, which, in spite of some amused comment on the star’s limited emotional range, he apparently found interesting: it was shelved because of censorship difficulties. Arthur Mizener names the films on which, on and off, he did some work: A Yank at Oxford, The Women, Madame Curie, Gone with the Wind, Raffles. M.G.M. dropped his contract after taking up the first option. They had used him, as one might expect, on “big” pictures, but rather as an odd job man, called in to tinker with a script, than as a creative writer. Bad luck, bad judgment, Fitzgerald’s own temperament and state of health, must have been to blame for this abortive career. But Hollywood traditionally breaks its writers by indifference, and the system does not encourage the fitting of the individual to the subject he can best handle.

The most notorious episode in Fitzgerald’s screen writing career is that used by Budd Schulberg in his novel The Disenchanted. Schulberg, then a young script writer, and Fitzgerald were despatched by Walter Wanger to a college weekend which was to figure in a musical, Winter Carnival. Schulberg’s story gives a bitter, tragic picture of the writer, employed solely for the cachet which his presence is supposed to give the producer in college circles, wandering drunkenly, incoherently around, extemporising fragments of an impossible script, shepherded and pitied by his rather reproving, governess-like young collaborator, until the producer finally packs him off to New York.

In 1940, Fitzgerald found a more attractive job. Lester Cowan bought one of his short stories, Babylon Revisited, and Fitzgerald was employed on the script. The story, of a jazz age expatriate’s return to Paris, his efforts to recover his daughter from a sister-in-law who blames him for his wife’s death, the destruction of his hopes, casually and completely, by two survivors from the past, is, in its acute and agonising sense of despair and regret, one of Fitzgerald’s finest. He said that his work on the script was “more fun than I’ve ever had in pictures”. The film was to be called Cosmopolitan. But Shirley Temple was wanted for the child’s part, was not available, and the plan was shelved. Since then Fitzgerald’s script has apparently been considered for publication, and a few months ago the Motion Picture Herald reported that Paramount had bought the rights of Babylon Revisited. One must assume that Fitzgerald’s own script will never reach the screen. It was almost his last job as a screen writer.

A Stahr is born

To accuse Hollywood of wasting Fitzgerald would be foolish; his strong visual sense, his superb dialogue, his undoubted interest in the mechanics of the film, suggest that he might have been employed to better purpose. But the facts of the case may have been more complicated. Instead, he turned to a novel, The Last Tycoon, strangely and impressively free from that angry resentment which runs through so much Hollywood fiction, from Nathanael West to Huxley. Previously – he had a taste for the histrionic – he had approached the cinema in short stories, through characters in the novels: here he tried to come to terms with the whole mystique of Hollywood.

In 1922, a character in The Beautiful and Damned, the enigmatic vulgarian film producer, Bloeckman, who effects the final humiliation of both Gloria and Anthony, symbolised the strange new forces of big business. In Tender is the Night it is through the resilient; hopeful young actress, Rosemary, “catapulted by her mother on to the uncharted heights of Hollywood” that we are introduced to the enchanted, exhausted, decaying world of the Divers. Rosemary herself, one feels, will be subject to a cruder corruption.

Fitzgerald approached the centre more nearly in a short story, Crazy Sunday, written after his second Hollywood visit. The unreality, the suspicion and self-destruction of Hollywood people are caught with the precision and tension that marks all his best writing. In the director who “meshed in an industry, paid with his ruined nerves for having no resilience, no healthy cynicism, no refuge”, there is an indication of the price which, he believed, Hollywood demands of those who resist its conditions.

Edmund Wilson says of California, “all visitors from the East know the strange spell of unreality which seems to make human experience on the Coast as hollow as the life of a troll-nest where everything is out in the open instead of being underground”. The typical Hollywood novel has that unreality – for the writer, Hollywood has proved only a precarious substitute for the real world. The standard hero is the disillusioned novelist himself, examining with horrified amazement the stages of his escape from the lures and betrayals of California. Fitzgerald, however, chose to write not as an exile or a tourist but from within. His narrator, the producer’s daughter, belongs to the first generation that could grow up with the industry, and her viewpoint is made explicit: “I accepted Hollywood with the resignation of a ghost assigned to a haunted house. I knew what you were supposed to think about it, but I was obstinately unhorrified.” The approach is echoed in the tone and pitch of the writing; the intimate, conversational style handled so flexibly that it retains an objective detachment, a wide angle of vision.

The novel has a particular context and perspective. Stahr is based on one of Hollywood’s almost legendary heroes, the late Irving Thalberg. Thalberg, who died in 1936, was in charge of production at M.G.M. (the position now held by Dore Schary); he is credited with that power of organisation, care for detail, and knowledge of when to spend money, allied to a taste for quality, that make the great impresario. Concerned as he was with the locus of power in Hollywood, Fitzgerald felt that it had shifted away from the director. ln his notes he wrote of Stahr:

“His relation with the directors, his importance in that he brought interference with their work to a minimum, and while he made enemies – and this is important – up to his arrival the director had been King Pin in pictures since Griffith made The Birth of a Nation… When he interfered, it was always from his own point of view, not from theirs. Thus his function was different from that of Griffith in the early days, who had been all things to every finished frame of film.”

Stahr’s authority, all powerful in the world he has made, dominates the novel. Self-made and semi-educated, his understanding of pictures instinctive rather than technical, he provides a directed, unifying control. Fitzgerald pays particular attention to his relations with writers; there is the scene in which he explains to the disillusioned English writer, Boxley – who represents the characteristic intellectual condemnation of an art so hedged about by conditions and compromises – that to make pictures one must learn and respect their language. Stahr’s own conception of his function has a naive, illuminating grandeur. “I never thought I had more brains than a writer has. But I always thought that his brains belonged to me – because I knew how to use them. Like the Romans – I’ve heard that they never invented things, but they knew what to do with them. “

Money is never far from the forefront of his world, and Stahr holds his ground because he has persuaded the money men to a temporary acceptance of his dictatorship. There is a specifically Hollywood idealism in the scene in which Stahr rocks the deepest convictions of the financiers by his plan to make a film that is bound to lose money. He has “moved pictures sharply forward through a decade, to a point where the content of the ‘A productions’ was wider and richer than that of the stage”. His responsiveness appears in the curious incident of the Black man, coming down to the beach to read Emerson, who, by his casual rejection of the movies, persuades Stahr to reconsider his whole production schedule.

Stahr himself cannot survive and Fitzgerald – writing in 1940 – saw his novel as “an escape into a lavish, romantic past that perhaps will not come again into our time”. The industry has grown too complex for the role of the paternalistic employer, with his intense faith in personal relationships and his understanding both of the financial strategy and of the picture itself. Stahr’s dream, like Gatsby’s, belongs in the past. Fitzgerald died with the novel only half-written, but Stahr’s defeat was to be brought about at the hands of the ruthless financier Brady, who neither knows nor cares about the making of films. Defeat comes to Stahr from within, in the loss of his health and control, and from both sides: Brady and his confederates are able to ally themselves with the unions. Stahr, the last tycoon, falls before the increasingly mechanistic, inhuman development of the industry.

His benevolent tyranny is exercised in a world not customarily taken seriously. But the power of Hollywood is a fact, and the novel, accepting it as such and alive to the possibilities and dangers, compels consideration of its nature. Fitzgerald’s dying, solitary, tragic hero is placed at the centre of an authentic battlefield

Stahr, by character and by circumstances, is majestically isolated. Around him are the down and out producers, second-rate writers, has-been stars still searching for their vanished glory, cut-throat business men who retain the standards of the circus tent, sycophants and swindlers. The moral atmosphere is one of corruption and a tired, jaded indifference. Only the financiers and the technicians habitually know where they are going, and an occasional Stahr, able to set in motion, to direct, to “care for all of them”.

This is the Hollywood with which Fitzgerald leaves us. His experiences of it are worth documenting because Scott Fitzgerald, sharing as he did that heightened awareness and responsiveness which he gave to Gatsby, could perhaps express more acutely than others the simultaneous attraction and repulsion that the novelist is likely to feel. The achievement of Hollywood is a fait accompli; an industrial civilisation’s inordinate demand for entertainment has been met; barriers of taste have been shattered to impose a new democracy: in the sight of the film, all audiences are equal. The cost has been enormous in waste, in misdirected energy, in the fatal attraction the cinema holds for the second-rate. The novelist wants at once to get his hands on the new medium and to rebuild the barriers. All this Fitzgerald sensed and recorded. In The Last Tycoon, in Stahr’s persuasion of Boxley, he perhaps found his own solution.

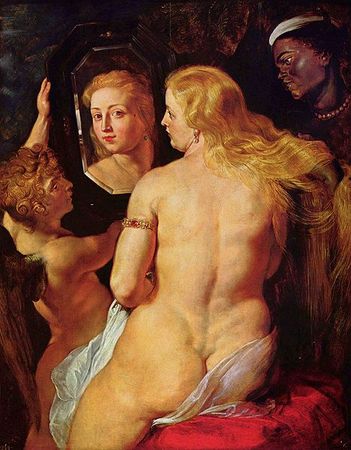

Vénus à son miroir par Rubens vers 1616

Vénus à son miroir par Rubens vers 1616![[manet_bar_at_folies_bergeres-1881.jpg]](https://blogger.googleusercontent.com/img/b/R29vZ2xl/AVvXsEjgfBrRrFp7MWAitWv1gooto6KL54vItoAonGnZaKPLIf8T8Nrftqs4nu9qDCVKV-U7Tm5B6fFUibLlNwNhTjY99XGjqr8WI6k-hgCPh9EIsQTXhuYqsjotMvCA6NSfsIhcyen1JgOgm5g/s1600/manet_bar_at_folies_bergeres-1881.jpg)