10 Fascinating Facts About the Belle Époque

1. The Belle Époque was an era of peace and plenty between wars

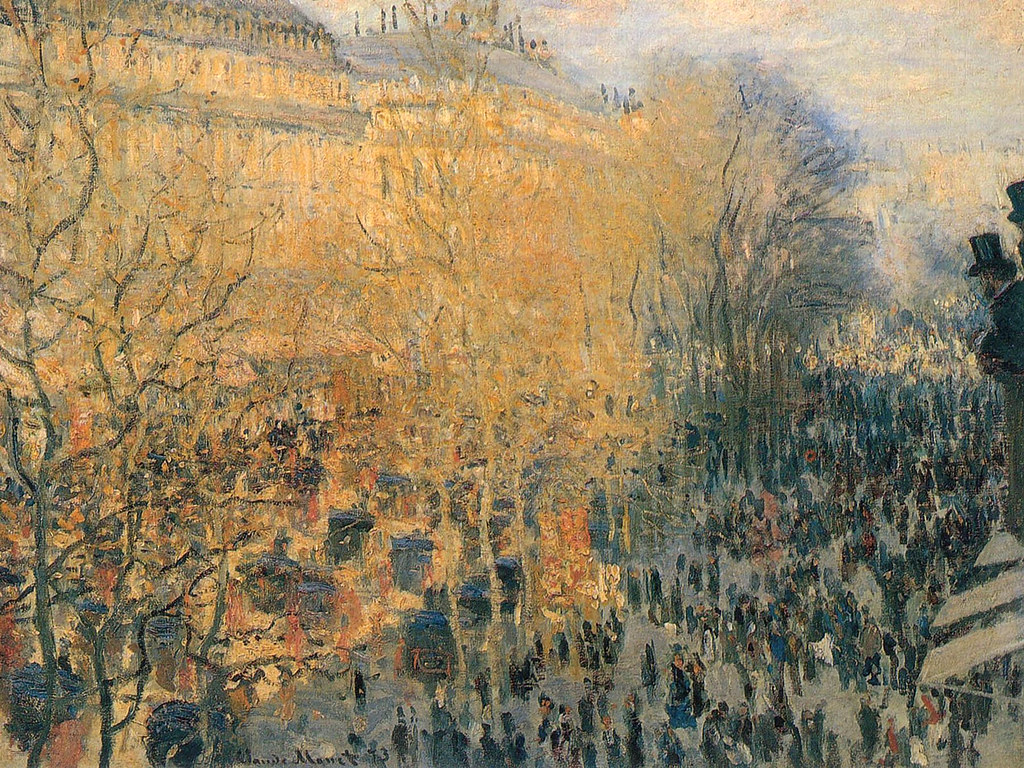

The French expression Belle Époque was used in retrospect after the horrors of World War One—a term of nostalgia for a simpler time of peace, prosperity, and progress.

At the beginning of the Belle Époque, France was recovering from defeat in the Franco-Prussian War—a defeat of staggering proportions. In just 9 months, France suffered 138,871 dead, 143,000 wounded, and 474,414 captured—a total that was more than six times that of the Prussian opposition.

In the wake of the Franco-Prussian War, Paris would suffer again through the Commune—a short-lived internal conflict between radical revolutionaries and the French Government. More tragedy and more loss, with estimates ranging from 7,000-20,000 revolutionary “Communards” killed.

Between the Paris Commune and the German heavy artillery bombing, Paris was a mess by the time a ceasefire was signed.

At the end of the Belle Époque, the winds of war were once again in the air. This time, it would be a thousand times worse.

One look at the devastation—hell on earth—and it’s easy to imagine every French soldier huddled, shivering in the filth of trench warfare, trying desperately to cling to the distant memory of a beautiful time—the Belle Époque.

2. It was a global phenomenon

Similar periods of economic growth were experienced in Britain during the late Victorian and Edwardian eras, in Germany under Kaiser Wilhelm I and II during the German Reich, in Russia under Alexander III and Nicholas II, in the United States in a period called the Gilded Age, and in Mexico during the Porfiriato.

Austrian-turned British, and Jewish banker, Baron Ferdinand de Rothschild’s weekend retreat of Waddesdon Manor in Buckinghamshire—built between 1874 and 1889—epitomizes the excesses of the era’s aristocracy in Britain.

Russian aristocrats enjoyed waltzing the night away at lavish balls in St Petersburg.

The Porfiriato was an era when Porfirio Díaz was president of Mexico from 1876-1911. He promoted order and progress that modernized the economy and encouraged foreign investment. The Porfiriato ended in 1910 with the outbreak of the Mexican Revolution.

The Gilded Age was a period of rapid economic growth in the United States—an era when anyone was a potential Andrew Carnegie, and Americans who achieved wealth celebrated it as never before.

3. It was an era of huge urban population growth

In the 39 years preceding 1911, the population of Paris grew by 64%. By the end of the Belle Époque, the population of Paris was higher than it is today.

New York’s population increased by 2 1/2 times from 1870 to 1900.

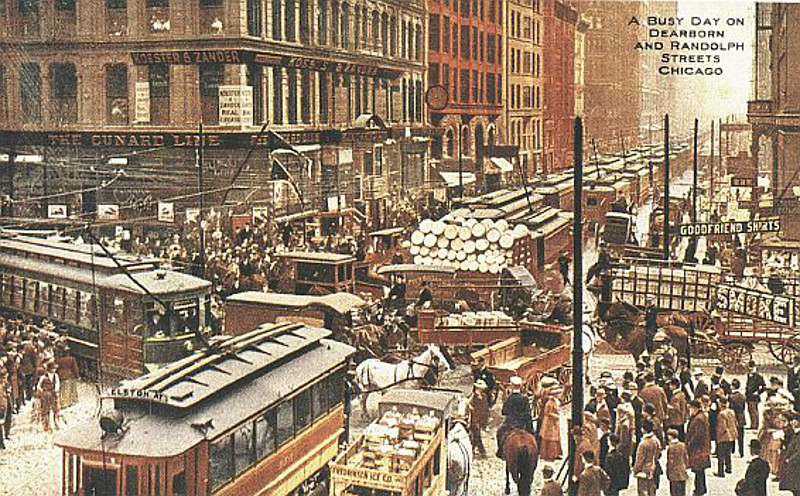

Chicago experienced even greater growth, with a staggering ten-fold increase in population between 1870 and 1900.

4. The Belle Époque was an era of progress and prosperity

With the humiliating defeat in the Franco-Prussian war a distant memory, the Paris Expositions of 1878, 1889 and 1900 celebrated France’s recovery.

At the Exposition of 1878, the gardens of the Trocadéro displayed the full-size head of the Statue of Liberty, before the statue was completed and shipped to New York.

Gustave Eiffel’s thousand-foot tower was symbolic of just how far France had come. It was the tallest manmade structure in the world and stood at the entrance to a showcase of French ingenuity and engineering mastery.

An equally significant building was the Machinery Hall. At 111 meters (364 ft), it spanned the longest interior space in the world at the time.

5. It was an era of cultural exuberance

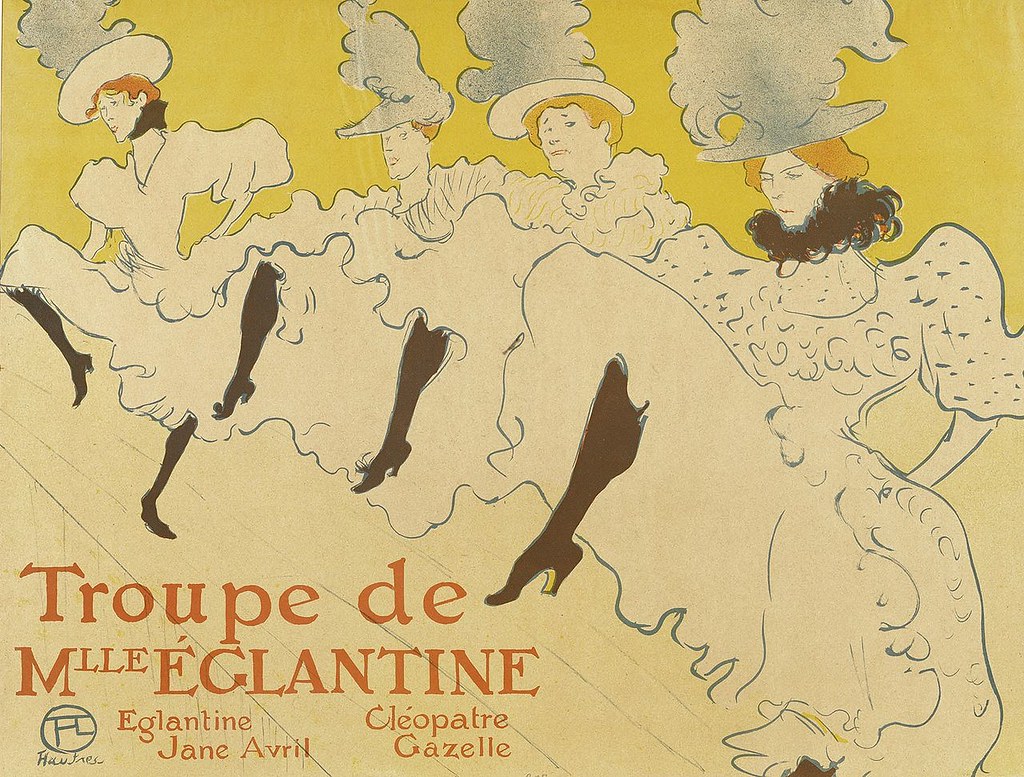

Marked by the red windmill on its roof, the Moulin Rouge is considered the spiritual birthplace of the modern version of the can-can dance.

Befitting the decadence of the times, the dance was considered scandalous and there were even attempts to repress it. Women wore pantalettes, which could be unintentionally revealing.

The club’s decor still holds the romance of fin de siècle (end of the century) France.

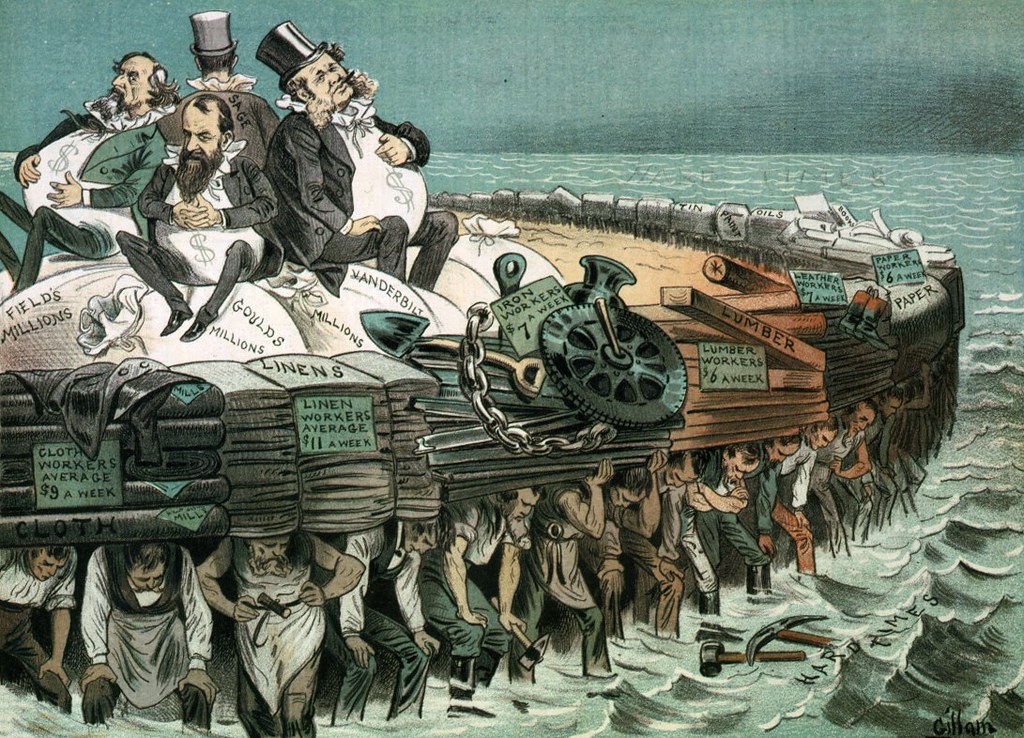

6. It was an era of rich and poor

Paris was both the richest and poorest city in France. An 1882 study of Parisians concluded that 27% of Parisians were upper- or middle-class while 73% were poor.

During America’s Gilded Age, the wealthiest 2% of American households owned more than a third of the nation’s wealth, while the top 10% owned roughly three quarters.

In New York, the opera, the theatre, and lavish parties consumed the ruling class. Mrs. Stuyvesant Fish once threw a dinner party to honor her dog who arrived sporting a $15,000 diamond collar.

In 1890, 11 million of the nation’s 12 million families earned less than $1200 per year; of this group, the average annual income was $380—well below the poverty line.

7. It was an era of scientific and technological advancement

The second wave of the industrial revolution seized the world.

Along came cameras, electric lights, the telephone, the gramophone, the automobile, and the dawn of air travel.

When Queen Victoria invited herself to Rothschild’s Waddeston Manor, it is said she was so impressed with the electric lighting that she spent 10 minutes switching an electric chandelier on and off.

8. An era of art and architecture

Although the architecture of the Belle Époque combined elements from several styles, the predominant architectural style was Art Nouveau.

A reaction to the academic influence of the Académie des Beaux-Arts, Art Nouveau (“new art”) was inspired by the natural forms and structures of flowers, plants, and curved lines. Architects tried to harmonize with the natural environment.

The Paris Exposition Universelle of 1900 was an Art Nouveau extravaganza.

9. The Belle Époque was an era of fashion

Jeanne Paquin was one of several fashion designers of the Belle Époque. She became known for her publicity stunts including sending her models to the races and the opera to get her designs noticed.

10. It was an era of Imperialism

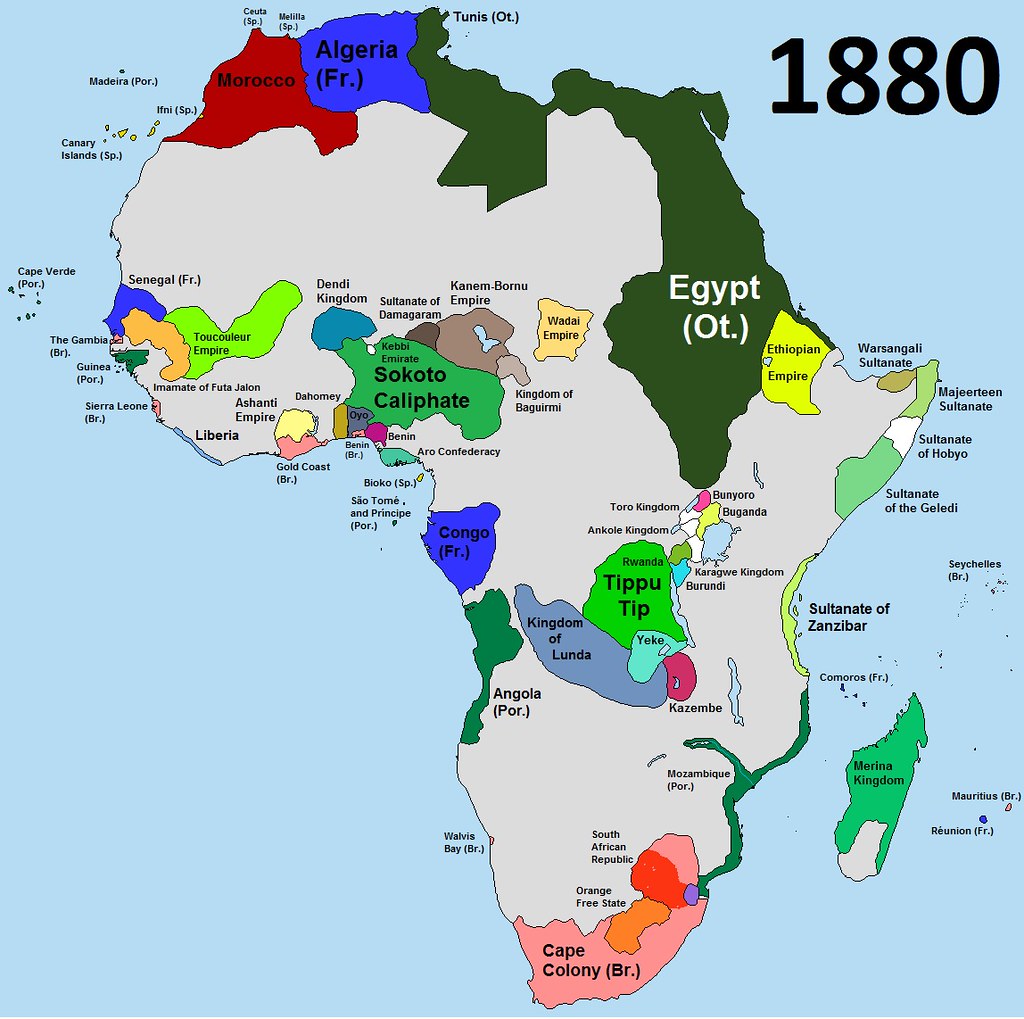

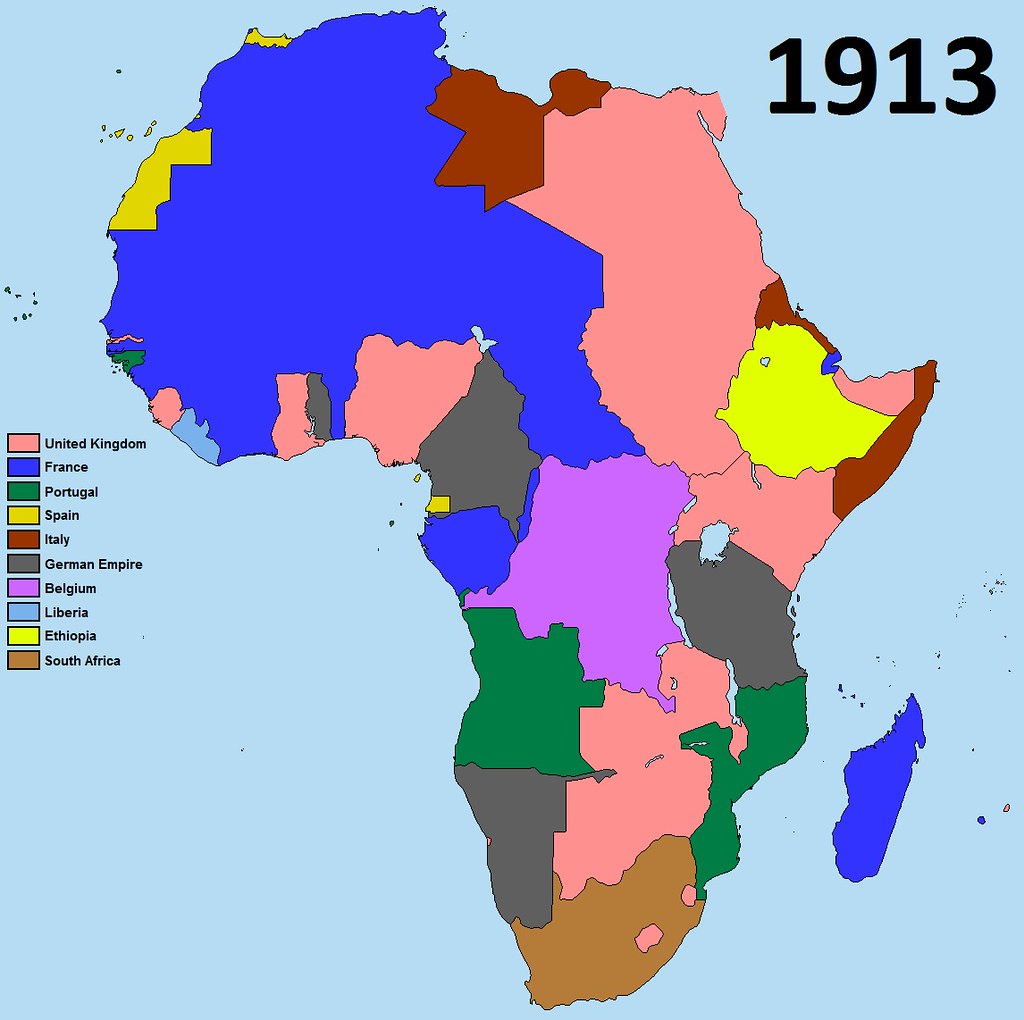

The “Scramble for Africa” was a race by European powers to colonize as much of Africa as possible in the latter part of the 19th century.

African land under European control went from 10% in 1870 to 90% in 1914.

1913, l'Europe à la fin d'une Belle Époque

By the end of the 19th century, Africa was one of the last regions of the world unaffected by Imperialism. That was about to change.

France and Britain in particular carved out huge swathes of land, with France concentrating on Northwest Africa and Britain wanting the eastern ports as stopovers for it’s Indian and Asian trade routes.

Cecil Rhodes was the man behind Rhodesia (now Zimbabwe) and the world-famous de Beers diamond company. His British South Africa Company acquired the land during the Belle Époque.

The Belle Époque was a beautiful era, but as Mark Twain described the Gilded Age, it was a thin veneer hiding systemic problems—discontent among the working classes, political tensions between nation states, militarism, imperialism, and to top it all, an unyielding arms race that by 1914 was a bubble about to burst. All that was needed was a trigger event.

https://fiveminutehistory.com/10-fascinating-facts-about-the-belle-epoque/

L’Europe, impérialiste et prospère, atteint en 1913 l’apogée de sa puissance. À la veille d’une guerre mondiale qui la laissera exsangue, elle s’impose comme le continent des innovations scientifiques, de l’effervescence artistique et du développement des idées socialistes.

L’EUROPE DU PROGRÈS EST UNE EUROPE IMPÉRIALISTE, RICHE, QUI PEUPLE LE MONDE

UNE EUROPE QUI PEUPLE LE MONDE

1913 marque une sorte d’apogée pour l’Europe occidentale. Son industrialisation rapide et les progrès qui en découlent lui permettent en effet d’être le premier continent à connaître la transition démographique : sa population augmente fortement car sa mortalité a chuté brusquement du fait des progrès de la médecine et de l’hygiène. L’Europe (y compris la Russie) passe ainsi de 265 millions d’habitants en 1850 à 450 millions en 1913, cette brusque croissance démographique obligeant les populations pauvres de nombreux États à émigrer : en 1850, 2,1 millions d’Européens décident ainsi de quitter le continent ; ils seront 6,7 millions en 1890 et 11 millions chaque année entre 1901 et 1910. Il faut ici noter l’exception française : en fait, la France ne connaît pas cette forte croissance démographique (36 millions d’habitants en 1850, 41 millions en 1913), ses habitants émigrent donc assez peu et le pays a recours à l’immigration pour remplir ses usines et trouver la main-d’œuvre nécessaire dans ses mines. Tous ces Européens émigrants vont peupler le monde – les États-Unis pour près de 30 millions d’entre eux, mais aussi l’Argentine, le Brésil, le Canada, l’Australie, les Antilles et l’Afrique du Nord. Cette émigration participe sans conteste à la mise sous influence du monde par l’Europe sous des formes diverses, la langue et la culture étant les plus évidentes. Ainsi, l’ensemble du continent américain voit disparaître les langues indigènes pour laisser la place à quatre langues européennes : l’anglais, l’espagnol, le portugais et le français. Il serait bien trop long de décrire la façon dont l’Europe a marqué en profondeur les sociétés américaines dans leur culture et dans leur organisation sociale et politique, mais on retiendra pour exemple la devise du Brésil, inscrite sur son drapeau : Ordem e Progresso (« Ordre et Progrès »), directement inspirée du philosophe positiviste français Auguste Comte.

UNE EUROPE SAVANTE

L’idée d’un progrès rectiligne et irrésistible caractérise l’Europe de la Belle Époque. C’est en effet ici que les découvertes scientifiques et technologiques se sont enchaînées durant un siècle, d’abord en Angleterre dès la fin du XVIIIe siècle puis en France et en Belgique. L’industrialisation a ensuite gagné l’Allemagne, l’Autriche-Hongrie, l’Italie, la Russie. À condition d’écarter l’Américain Thomas Edison, la plupart des inventions marquantes sont européennes : 1860, le moteur à explosion (Lenoir) ; 1871, la dynamo (Gramme) et le moteur à essence (Daimler-Benz) ; 1890, la TSF (Branly) et l’avion (Ader) ; 1895, le cinéma (frères Lumière) ; 1899, l’aspirine (Bayer)… L’académie Nobel ne détonne pas dans cette domination scientifique, au contraire, puisque, sur les soixante-sept prix décernés entre 1901 et 1913, seize le sont à des Allemands, quatorze à des Français et sept à des Britanniques, et quelques autres à des Hollandais, des Italiens, des Suisses ou des Belges. Seuls trois prix décernés à des Américains échappent à cette hégémonie – mais, à cette date, ces derniers sont encore des immigrés européens !

Conscients de ce progrès, les Européens cherchent à le célébrer dans de grandes Expositions universelles qui, en toute logique, se tiennent essentiellement sur leur continent. Si la première se tient Londres en 1851, les deux plus marquantes à Paris sont celles de 1889 et 1900, puis viennent Bruxelles (1910), Turin (1911) et Gand (1913). Par des exploits spectaculaires, les Européens démontrent qu’ils peuvent allier technologie et audace : Blériot traverse ainsi la Manche en avion en 1909 ; quatre ans plus tard, c’est Roland Garros qui traverse la Méditerranée. La puissance scientifique de l’Europe prépare en outre d’autres révolutions, comme à l’université de Manchester, où Ernest Rutherford identifie en 1911 la structure de l’atome, jusque-là réputé indivisible : cette discontinuité de la matière répond aux théories d’Albert Einstein, qui, la même année, formule une nouvelle loi de la gravitation universelle. Cette domination scientifique et technologique déjà ancienne permet aux Européens de dominer militairement le monde depuis le XVIe siècle. Néanmoins, depuis le XIXe siècle, la colonisation et l’exploitation du monde constituent un système plus mondialisé encore.

UNE EUROPE COLONIALE

Le fait de coloniser n’est certes pas réservé aux Européens, mais ce sont eux qui créent un système complexe, une exploitation économique accompagnée d’un discours la justifiant. Rudyard Kipling, dans un célèbre poème de 1899, Le Fardeau de l’homme blanc, évoque ainsi une justification raciale et morale de la colonisation : l’homme blanc doit assumer son « fardeau », sa responsabilité de « civiliser » les peuples et de faire cesser la misère. Outre la mission civilisatrice, on développe d’autres arguments : la christianisation, bien sûr, la recherche de marchés, la quête de placements intéressants et enfin la volonté de satisfaire un orgueil national parfois malmené (en particulier celui des Français après l’humiliant traité de Francfort en 1871).

Derrière ces discours, les Britanniques, les Français, les Portugais, les Belges et les Allemands ont bataillé pour se partager des terres réputées « vierges » afin de les exploiter. En 1913, 39,1 % des terres émergées sont dominées par des Européens, ce qui représente 554 millions d’habitants soumis, soit un tiers de l’humanité, l’Empire britannique demeurant la construction coloniale la plus vaste, où « le soleil ne se couche jamais » (voir L’éléphant n° 2).

UNE EUROPE PROSPÈRE

Ces empires coloniaux alimentent en matières premières les industries du continent tout en leur en offrant des débouchés et permettent aux Européens de connaître une prospérité inégalée jusqu’alors. Cette prospérité s’appuie sur une forte expansion des biens de consommation, puisque les nouveaux produits élaborés par l’industrie sont achetés par une population plus urbanisée et dont le niveau de vie s’est largement amélioré : produits alimentaires (biscuits, chocolat, thé, café, tabac), téléphones, gramophones, bicyclettes et automobiles se répandent, autorisant l’économiste John Maynard Keynes à écrire qu’« un habitant de Londres pouvait, en dégustant son thé du matin, commander par téléphone les produits variés de toute la Terre en telle quantité qui lui convenait ». Certes, tous ces biens ne sont pas encore accessibles à tous et partout, mais ils jettent déjà les bases d’une première société de consommation.

Les biens de production connaissent aussi une très forte progression, la production d’acier étant à cet égard assez révélatrice : les cinq premières puissances industrielles européennes produisent 34 millions de tonnes en 1913 contre seulement 11 millions en 1900. Quant à leurs produits manufacturés, ils sont exportés partout dans le monde grâce aux difficiles progrès du libre-échange mais également grâce à la navigation à vapeur (le steamer). Ainsi, l’Europe fournit à l’Afrique plus de 75 % de ses produits manufacturés. Cette domination industrielle et commerciale permet aux puissances du continent de devenir les « banquiers du monde » en possédant à la veille de la Grande Guerre plus de 60 % du stock d’or mondial. Mais ce sont avant tout les capitaux placés à l’étranger qui assurent des revenus confortables. En 1913, six pays européens (Royaume-Uni, France, Allemagne, Suisse, Belgique et Pays-Bas) détiennent 90 % des capitaux placés à l’étranger. Ces capitaux sont certes investis dans les colonies mais également dans les autres pays industrialisés et témoignent déjà d’une première mondialisation financière. Pourtant, l’Europe, si puissante soit-elle, doit faire face à des rivalités et à des doutes profonds.

https://journals.openedition.org/rh19/4997