Giovanni Battista Piranesi, dit en français Piranèse

Cet article est extrait de l'ouvrage Larousse « Dictionnaire de la peinture ».

Peintre italien (Mogliano Veneto 1720 – Rome 1778).

Graveur et architecte italien (Mogliano Veneto 1720-Rome 1778).

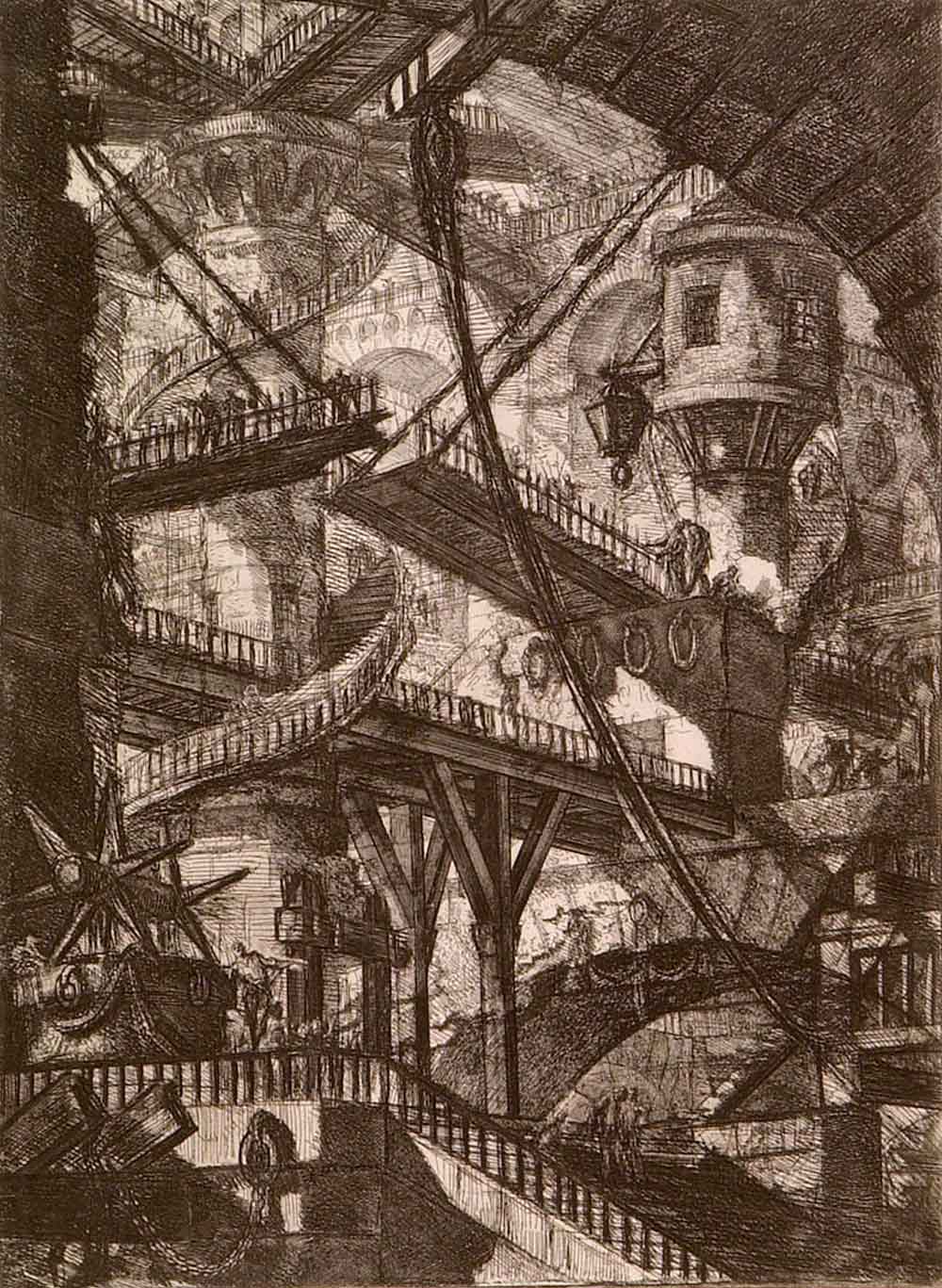

Formé à Venise comme bâtisseur et scénographe, établi à Rome en 1745, il a très peu construit, mais, par ses séries d'eaux-fortes récréant l'Antiquité de façon visionnaire (notamment les Antiquités de Rome, 4 volumes, 1756) ou en diffusant, avec éclectisme, les motifs décoratifs (Diverses Manières d'orner les cheminées, 1769), il a été l'un des catalyseurs du néoclassicisme. Sa vision du passé comme le caractère dramatique de ses Prisons (1745-1760) font aussi de lui un précurseur du romantisme.

Il reçut sa première formation à Venise, où, ayant décidé de se consacrer à l'architecture, il étudia auprès de différents architectes et scénographes. C'est par ailleurs auprès d'un graveur qu'il apprit, selon l'usage de l'époque, ses premiers rudiments de perspective. Il fut sans doute marqué, pendant cette période, par le climat néo-palladien dans lequel se développait l'architecture vénitienne ainsi que par la connaissance de Bibbiena, dont il dut lire avec passion l'Architettura civile, parue en 1711. En 1740, il était à Rome à titre de dessinateur de l'ambassade vénitienne : c'est là que, pratiquant la gravure dans différents ateliers spécialisés et ayant accès à la célèbre collection d'estampes du cardinal Corsini, il s'orienta de façon décisive vers l'eau-forte, technique qu'il allait adopter comme son unique moyen d'expression. (Piranèse eut aussi une activité d'architecte, qui resta toutefois secondaire et qui fut surtout une application des principes énoncés dans ses gravures.) En 1743, date de la publication de la Prima Parte di architetture e prospettive, une culture vénitienne essentiellement architecturale se révèle dans ses planches aux constructions grandioses, où son imagination, déjà fertile, est guidée par le souvenir de ses expériences dans le domaine de la scénographie. De retour à Venise la même année, Piranèse fréquenta, selon certaines sources, l'atelier de G. B. Tiepolo. C'est donc à partir d'un substrat vénitien que prit naissance la vision de celui qui allait devenir l'un des représentants les plus significatifs de la culture romaine du xviiie s. C'est encore à Venise, en 1744, que Piranèse élabora ses premières idées pour les Caprices et les Prisons, dont il prépara les cuivres l'année suivante à Rome, mais qui ne furent publiés qu'en 1750 sous le titre d'Invenzioni Caprici di Carceri. C'est en 1745 également qu'il aborda pour la première fois le thème de la " veduta ", avec 27 petites planches publiées dans un recueil d'illustrations de Rome par l'éditeur Amidei : en même temps que son génie de visionnaire se déploie librement dans les divagations nocturnes et hallucinantes des Prisons, l'artiste affronte la représentation d'après nature selon les règles de la " veduta " réaliste, dont Rome revendiquait à juste titre la paternité. On peut déceler là le conflit entre l'attrait spontané pour le fantastique de Piranèse poète et l'exigence d'objectivité de Piranèse érudit, bientôt archéologue et théoricien, conflit qui conditionnera dorénavant toute l'activité de l'artiste en donnant à son œuvre cette puissance de suggestion à laquelle l'Europe entière sera sensible.

Les 30 planches des Antichità romane dei tempi della Repubblica, publiées en 1748, sont le premier fruit de cette dialectique ; la critique y voit par ailleurs le moment où les liens du maître avec Venise se relâchent pour faire place à une participation plus directe à la vie culturelle romaine. Il est certain que les intérêts archéologiques de l'artiste y prennent une forme plus concrète et que le sujet même de la publication annonce clairement la prise de position théorique qui fera de Piranèse l'adversaire déclaré du programme archéologique de Winckelmann et de ses adeptes. Avec Piranèse, le mythe de la Rome antique s'affirme avec la force évocatrice que seule une imagination passionnée peut alimenter ; à la lutte que le théoricien engage avec ses contemporains correspond le combat entrepris par l'artiste contre le temps, qui détruit et enfonce dans l'oubli les civilisations. L'eau-forte, dont le graveur perfectionne prodigieusement la technique, est mise au service de cette double bataille ; elle est non seulement un moyen d'expression, mais aussi un puissant instrument de propagande et de divulgation qui soulève des polémiques à l'échelle internationale. Ressusciter le passé en fixant sur le papier les images des monuments antiques découverts par les fouilles et des ruines majestueuses qui servent de cadre à la vie contemporaine, établir des répertoires et proposer des reconstitutions archéologiques, telles sont les tâches qui occupent de façon obsédante les trente dernières années de la vie de Piranèse. Il ne lui en faut pas moins pour terminer les deux volumes des Vedute di Roma, commencées en 1748 et parues l'année de sa mort. Entre-temps, il achève les 4 tomes des Antichità romane, qu'il publie en 1756 ; il donne une forme encore plus tourmentée et angoissante à ses visions dans la seconde version des Carceri d'invenzioni, gravés et publiés en 1760-61 ; il édite son principal traité théorique : Della magnificenza ed architettura dei Romani, illustré de 38 planches qui commentent de façon éloquente la thèse soutenue par l'auteur, à savoir que, " en fait d'architecture, les Romains n'ont été redevables que de peu ou de rien aux Grecs " (1761) ; il joint la spéléologie à l'archéologie pour réaliser l'ouvrage Descrizione e disegno dell'Emissario del Lago Albano (1762-1764), dont les 9 planches lui permettent de rattacher au réel les abîmes obscurs et souterrains de ses rêves ; il élargit son champ de recherches aux villes de Cori (Antichità di Cora, 1764) et de Paestum (Différentes Vues de l'ancienne ville de Pesto, 1778) ; il rassemble les recueils Diverse Maniere d'adornare i camini ed ogni altra parte degli edifizi (1769) et Vasi, Candelabri, Cippi, Sarcofagi, Tripodi, Lucerne ed Ornamenti antichi (1778), destinés à devenir dans toute l'Europe l'un des répertoires les plus importants des motifs du Néo-Classicisme.

La personnalité de Piranèse occupa une place assez particulière dans la culture européenne du xviiie s. : tout en s'opposant à la légèreté frivole du Rococo, l'artiste refusa les idéaux simplistes auxquels semblait vouloir s'arrêter l'archéologie au moment où elle prenait forme de discipline scientifique. La portée philosophique de son œuvre, visant à saisir les aspects contingents de l'histoire pour les revitaliser à travers l'image que lui en offrait sa conscience d'homme moderne, fut fondamentale pour les générations qui le suivirent ; sans doute n'a-t-elle pas encore cessé, aujourd'hui, d'exercer son influence. L'érudition récente a mis en valeur le rôle qu'il exerça sur les jeunes Français à Rome (Desprez, Legeay, Le Lorrain).

Piranèse fut un admirable dessinateur, l'un des plus grands du xviiie s. italien avec Tiepolo. Ses dessins, généralement à la plume et au lavis, parfois à la sanguine, sont le plus souvent des études d'ensemble ou de détails (personnages), préparant plus ou moins directement ses vues gravées. Griffant le papier avec une vivacité et parfois une nervosité stupéfiantes, jouant, comme dans ses estampes, des contrastes lumineux fournis par l'opposition de traits minces et de zones fortement encrées, Piranèse saisit la complexité d'un vaste paysage ou l'essentiel du geste d'un minuscule personnage avec la sûreté d'œil du visionnaire.

Parmi les cabinets des dessins conservant des feuilles particulièrement impressionnantes, citons ceux de Hambourg, de Copenhague, de Berlin, du British Museum, des Offices, du Louvre et l'E. N. B. A. de Paris.

---------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------

Piranesi and the Gardens of Rome

detail from the Villa Albani

Italy has always been famous for its classical monuments and, since the Renaissance, for its gardens too. Both attracted tourists in growing numbers, particularly as the Grand Tour became an essential part of the education of almost every young northern European member of the elite.

Aristocratic or not tourists have always wanted souvenirs. Some wanted to take home antique sculptures, others to have their portraits painted in Italian settings by Italian artists, but others less wealthy had to be content with buying prints, and so the production of engravings of the major sites, towns and landscapes became a lucrative business.

The greatest exponent of these views – or vedute as they are known – was Giovanni Battista Piranesi who possessed “one of the most imaginative minds ever to have brooded on the visual arts”.

detail of the Villa Pamphili

Such was the power of Piranesi’s imagery that these vedute created a lasting impression of Rome almost as magnificent as it must have been in the days of the Caesars. However, they didn’t match with reality so it’s quite likely that tourists who saw his engravings before they saw the actual sites themselves would probably have been disappointed!

Piranesi obviously loved Rome which is perhaps surprising since he was born near Treviso in the Republic of Venice in 1720. His father was a stone mason and his uncle an architect so he grew up in a world of building, constructions, plans and sketches, and was probably assured a job alongside one of them. However when in about 1740 he had the chance to go as a draughtsman to Rome with the Venetian Ambassador to the papacy he grabbed it.

The Temple of the Sibyl at Tivoli

So where did this enthusiasm for Rome come from? Probably because of a shift in the balance of cultural power between the two cities. 18thc Venice was atrophied, and although it remained a permanent attraction of the the Grand Tour the centre of intellectual exchange was shifting to Rome. The Eternal City attracted not just tourists and the artists and dealers who served them, but antiquarians and architects like Robert Adam and John Soane who came to study the ruins.

Title page of the 1st edition of Prima parte di Architettura e Prospettive, 1743

On his arrival in Rome Piranesi lived near the French Academy in Rome which had been established by Louis XIV as a “finishing school” for aspiring French artists. He began by studying for a short period under Giuseppe Vasi, an architect turned engraver who was already publishing vedute, and was to go on and produce several volumes of them in book form. But Piranesi was clearly anxious to test his own talents.

Prima parte di Architettura e Prospettive his first collection of a dozen or so prints of fanciful reconstructions of imaginary classical buildings was published in 1743. The images bear similarities to contemporary theatre set designs, notably in the use of exaggerated perspective, which he was to use to great effect in his depiction of gardens. The collection was not a great commercial success although it was reissued in a revised form a few years later and some of the prints were recycled and appeared in other volumes.

Piranesi left Rome after it was published, returning to Venice, before travelling to see the excavations which had begun in 1738 at Herculaneum. He returned to Rome in 1745.

By then he had met with many of the students at the French Academy, and working with a group of them, he produced another series of engravings: Varie Vedute di Roma Antica e Moderna in 1745.

The Villa Ludovisi from Varie Veduta. The Gardens were designed by Le Notre

This was reissued in 1748 as Antichita Romane and quickly earned Piranesi an international reputation. The plates were enormous in scale and printed on the finest quality paper.

Around the same time Piranesi opened his own workshop, and in 1751, 34 more views of Rome appeared as Le Magnificenze di Roma. In 1761 he acquired his own printing press which gave him control of the whole process from site measurement and drawing to the materials he used, and then engarving, printing and publishing. A further 135 prints gradually appeared over the next 25 years.

Around the same time Piranesi opened his own workshop, and in 1751, 34 more views of Rome appeared as Le Magnificenze di Roma. In 1761 he acquired his own printing press which gave him control of the whole process from site measurement and drawing to the materials he used, and then engarving, printing and publishing. A further 135 prints gradually appeared over the next 25 years.

Nowadays the ancient monuments of Rome are well-protected but this was absolutely not the case in Piranesi’s day and most were abandoned in fields and gardens, and many had plants growing all over them.

Even the central area around the Forum was simply known as the Campo Vaccino – the Cow Field. The ruins evidently appealed to a growing antiquarianism within Piranesi, and his visit to Herculaneum and the new excavations at Pompeii in the 1740s added to that interest. In 1751 he was even to become become director of the museum set up to house the finds.

Piranesi’s work was certainly realistic but it was also antiquarianism writ large. He measured many of the buildings he engraved, the better to appreciate their construction and engineering. This enabled him to “fill in” the missing details of ruins, as well as faithfully capture their scale and appearance. Combined with his skill at manipulating light and shade he gave his subjects a romantic, almost gothic, feel despite their classical origins. In a way his engravings can be seen as an attempt to “preserve” the ruins and certainly it’s true they allow people to experience the “rustic” atmosphere of 18thc Rome.

As Kerrianne Stone points out in The Piranesi Effect, gardens, vegetation and landscape settings are prominent in many of his images of ruins and even the palazzi – and his use of nature, the way he places trees and plants on and around the ruins anchors them in reality, at the same time as anchoring them back to nature. There’s no doubt that the vegetation heightens the impression of decay and without “the vegetal stalactites that festoon the crumbling vaults … these scenes would lose much of their gravity.”

Now it’s about time I started talking about some of the gardens which are included in the views. although there are only a handful which are specifically designed to show them.

The Villa Albani

The Villa Albani featured in a print of 1769. It was a huge new palace built between 1745 and 1767, just outside the old city walls for Cardinal Albani, who was the nephew of Pope Clement XI. The cardinal had a series of small vineyards consolidated into a single plot and commissioned Giovanni Battista Nolli, to lay out a garden. The villa was primarily to house Albani’s vast collection of ancient sculptures and he employed Johann Winckelmann the great classical scholar to catalogue, arrange and research them. It quickly became a big attraction for those on the Grand Tour with people flocking to see the sculptures displayed not only inside but on the terraces and in the garden too. That may be the reason Piranesi added the villa and garden to what was otherwise largely a collection of ancient monuments.

detail from Villa Albani

The garden is seen from an oblique angle, which distorts the view in much the same way as a wide angle lens might do. Piranesi doesn’t show the whole garden, and there is probably more missing than included. The view ends with the large Fontana dei Facchini, with its four Atlas figures. This is now in the Louvre, part of the loot taken to Paris by the French in 1797, and unlike smaller works of art was considered too expensive and complicated to return after Napoleon’s defeat in 1815. The garden extends further to the right of the print and ended with a large pavilion called the Caffeaus [or coffeehouse] which had a grand semi-circular portico.

The site was originally relatively flat but Nolli created a sunken garden to display the cardinal’s treasures. It had a double axis, grand fountain and two streams running its length from the palace to the southern entrance with a statue of Amphitrite, the wife of Poseidon the sea god, as the focal point of a series of cascades. There is a detailed description by Tom Turner

detail from the Villa Albani

Of course tastes change and a century later Henry James, the American novelist visited in 1873 and was less than impressed: “Yesterday to the Villa Albani. Over-formal and (as my companion says) too much like a tea-garden; but with beautiful stairs and splendid geometrical lines of immense box-hedge, intersected with high pedestals supporting little antique busts….And yet a Roman villa, in spite of statues, ideas and atmosphere, affects me as of a scanter human and social portée, a shorter, thinner reverberation, than an old English country-house, round which experience seems piled so thick. But this perhaps is either hair-splitting or “racial” prejudice. ”

detail from Villa Albani

One of the interesting features of this print is that amongst the most prominent of the people shown are Albani’s gardeners. They are also the most animated. As Colin Holden points out in the video below this might not be so surprising when you know that Piranesi’s wife, Angelica, was the daughter of a gardener to Prince Corsini.

The Villa Albani [now Villa Albani-Torlonia] somehow escaped destruction as Rome grew round it and although parts of the garden have been sold and developed, it’s now Rome’s only example of an 18th-century villa still in a more or less pristine state. What remains is still well maintained although until recently the villa and its gardens have not been open to the public. There is an article by Clive Cookson in the Financial Times in May 2019 describing the gardens today, and explaining how this was now changing with “free” visits bookable in advance with a suggested “donation” of least €50.

The Villa Albani today

The Villa d’Esté in Tivoli originally built for Cardinal Ippolito II d’Este in the 16thc was the subject of another etching published in 1773. The Villa was a sort of consolation prize for his not being elected pope and the cardinal splashed out huge sums on rebuilding a former monastery and laying out the grandest of grand Renaissance gardens down the hillside in front of the house. It required vast amounts of engineering and earthmoving to pull off such a seemingly effortless playing with space,

Villa d”este

Tivoli is the meeting place of three of the Tiber’s spring-fed tributaries and so the gardens of the Villa d’Este are dominated by water which is used to power the garden’s array of cascades and fountains and even a water organ.

Tivoli is the meeting place of three of the Tiber’s spring-fed tributaries and so the gardens of the Villa d’Este are dominated by water which is used to power the garden’s array of cascades and fountains and even a water organ.

Piranesi’s view focused on the garden, and looks straight down the central axis up to the villa on the summit outlined against the sky. Water dominates the garden, the fountains are shown in full working order with water gushing out and cascading through the network of paths that take the visitor down the steep slope from the villa. Vast engineering and earthwork was required to pull off such a seemingly effortless play of space,

On the the central “vertical” axis you can see the Fountain of Gentle Dragons, and the multi-storied Fountain of the Cups and lower down, running across the garden is the misleadingly named Alley of a Hundred Fountains which links two more grand fountains. [Misleading because there are actually 300] It has water sprays and jets spouting out from eagles, boats and animal mouths, into three canals.

Piranesi uses artistic license to reveal the scale of the site. His drawing was made from the centre of a circle of cypress trees which he did not include because had he done so they would have obstructed a complete view of the site. Several of these trees still survive.

detail from Villa d’Este

He further emphasised the scale of the site by distorting the perspective, with the fountains and statues in the foreground shown larger than reality, while most of the figures portrayed are drawn much smaller.

detail from Villa d’Este

Two years later, in 1776, Piranesi published another impressive view, this time of the baroque Villa Pamphili. This started life as the country house of the Pamphili family, again just outside the Roman walls, but when Giambattista Pamphili was elected Pope Innocent X in 1644, it wasn’t grand enough for his new status and a new palace was commissioned. This was surrounded by extensive grounds with a lemon grove, some follies and a water-filled grotto.

This time Piranesi chose an oblique viewpoint far above the site. This gives good sense of its scale, whilst he also played with perspective, reducing the size of the people strolling among the parterres, and exaggerating the trees which frame the scene.

The gardens of the Villa Pamphili, were later extended by the acquisition of neighbouring properties and are now Rome’s largest park, and can be seen in great detail in an Italian documentary about them available on youtube.

Sadly although Piranesi considered his real metier was as an architect he did not really get many opportunities to practice. The pope asked him to submit designs for the restoration of a church but, in the end, did not commission him to do the work.

The boundary of the piazza also designed by Piranesi

However the pope’s nephew Cardinal Rezzonico, offered him the chance to restore another church, Santa Maria del Priorato, and create the piazza on which it stands. This may have been the reason Piranesi was awarded a papal knighthood in 1767 and become a Cavaliere. The church is also where he is buried. Irene Small has written a detailed architectural analysis .

The Piranesi Vase

If Piranesi did not build actual buildings he certainly imagined them. Not content with simply recording and copying what he saw, his imaginative genius also led him to invent. His fictitious monuments, objects and scenes are now probably better known than his images of real things. Amongst them are the highly architectural “Prison” engravings and the gigantic “Roman” vase, the ultimate fake antique for an English stately home, now known as the Piranesi Vase now in the British Museum.

Piranesi’s legacy was ensured by his son and collaborator, Francesco, who saved the printing plates, and re-used them to publish Twenty-nine folio volumes containing about 2000 prints in Paris (1835–1837).

For a comprehensive overview of Piranesi’s work see Luigi Ficacci’s Piranesi: The Complete Etchings, published by Taschen, [undated]. For more on Piranesi, Arcadia and the Theatre see, Susan Dixon’s article “Vasi, Piranesi and the Accademia degli Arcadi”, in Memoirs of the American Academy in Rome (Vol.61 2016)

Gardeners at work on a fountain in the gardens of the Villa Albani

Publié pour la première fois en 1918, cet ouvrage consacré à l'architecte-graveur Giovanni-Battista Piranesi (Mestre 1720 - Rome 1778) est plus qu'une biographie. Il s'agit d'une véritable étude de la société italienne et romaine au XVIIIe siècle qui, sur bien des points, fait encore autorité aujourd'hui.

Publié pour la première fois en 1918, cet ouvrage consacré à l'architecte-graveur Giovanni-Battista Piranesi (Mestre 1720 - Rome 1778) est plus qu'une biographie. Il s'agit d'une véritable étude de la société italienne et romaine au XVIIIe siècle qui, sur bien des points, fait encore autorité aujourd'hui.

Fils d'un tailleur de pierre vénitien, Giovanni-Battista Piranesi reçut une formation d'architecte. Passionné par l'antiquité romaine, il accompagna, âgé de vingt ans, l'ambassadeur de Venise auprès du Saint-Siège à Rome. Il put alors satisfaire à loisir sa passion et parfaire sa formation auprès des maîtres romains. Lors de ce séjour, il s'initia à la gravure, art qu'il pratiqua sa vie durant, gravant des vues de Rome où les ruines antiques sont omniprésentes.

EXHIBITIONS

Piranesi: Imaginative Spaces

Piranesi is widely known for his lofty and often exaggerated views of Rome. But this series, The Prisons, or in Italian, Le Carceri D’Invenzione, are works purely from his imagination. His knowledge of architecture and his fine ability to produce great detailed and textured prints led him to this series.

Multiple versions (or states, as they are called) of the same image will be on view, to illustrate the changes made by the artist with each of the three printings. The series is quite interesting for its own sake, but the influence on contemporary artists working in the centuries that follows, creates a broader picture, expanding on its meaning.

Piranesi’s imagined architectural designs were one of many influences on Robert Morris that eventually led to the Glass Labyrinth, now housed in the museum’s Donald J. Hall Sculpture Garden.