Plague visionaries: how Rembrandt, Titian and Caravaggio tackled pestilence

Much of Europe’s greatest art is haunted by outbreaks – but amid the death are testimonies of love. Can these masterpieces guide us through today’s crisis?

I

t seems incredible that we should find common cause with the people of 500 years ago, who faced disease without any understanding or remotely adequate treatment. But on Sunday, Pope Francis walked the streets of Rome, left empty by coronavirus, to visit the church of San Marcello on the Corso – and revere a cross that supposedly protected Rome from plague in 1522.

We now find ourselves in the same plight – menaced by an illness that seems to have the upper hand and that is turning our assumptions upside down. Even the methods being used, including quarantine, come from that plagued past. As does much of Europe’s greatest art. These masterpieces might console us, or make us see this unfamiliar moment in a new light, or even give us practical ideas to cope. Here are some of those images, perhaps to be used as guides – for Rembrandt, Titian and Caravaggio trod this path before us.

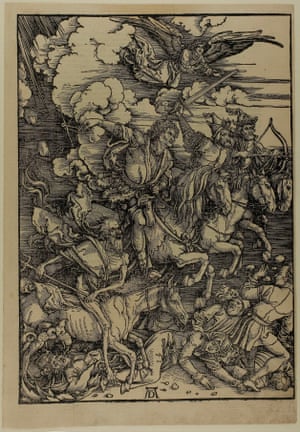

Albrecht Dürer: The Four Horsemen of the Apocalypse (1498)

Death and his three henchmen ride roughshod over the world, crushing popes and peasants under their horses’ hooves. This woodcut visualising The Book of Revelation identifies humanity’s three worst killers: war, famine and pestilence. The horseman with a balance probably represents pestilence, though sometimes he’s identified with the archer, for the arrows of a plague strike unseen, as if from a distance, and without warning. In Dürer’s world, this was the most feared of the horsemen. In 1347, Genoese ships brought a devastating plague to Europe from the Crimea. In the next few years, the Black Death killed at least a third of the continent. After this initial pandemic, the plague regularly returned to European cities. Recent DNA tests on skeletons from London and elsewhere confirm that all of these outbreaks were bubonic plague, caused by the bacterium Yersinia pestis.

Salvator Rosa: Human Frailty (c1656)

Every city in early modern Europe suffered returning epidemics that could kill from 10-50% of a population. It’s thought at least half the inhabitants of Naples – more than 200,000 people – died of plague in 1656. Rosa’s painting is a report from death’s front line. It might seem the ultimate in macabre overstatement: a newborn baby writes an agreement with Death acknowledging that human existence is miserable and brief. Death is a terrifying skeleton with wings that loom up into the painting’s sepulchral darkness. Rosa survived the 1656 plague but lost his young son, along with his brother and sister, her husband and five children. The infant here is that young son, Rosaldo, accepting death’s dominion.

Titian: Pietà (1575-6)

An old man prays for his son and himself to survive an epidemic in this moving confession of desperation. Titian painted this twilit image when Venice was being ravaged by plague. He portrays himself half-naked, prostrated before the image of Mary cradling the dead Christ. To make his message clear, he includes a picture within this picture: a crudely daubed popular ex-voto panel you might see in a church, depicting him and his son Orazio in prayer. This most sophisticated of artists is offering this great ashen canvas in the same simple spirit as an offering any peasant might make. It didn’t work. Titian and Orazio both died in the 1576 plague.

Antonio Zanchi: The Virgin Appears to the Plague Victims (1666)

San Rocco or Saint Roch was regarded as a plague protector because he miraculously cured himself of infection. The Scuola Grande di San Rocco in Venice was built for a confraternity dedicated to him in a city where cramped conditions made it a hive of disease despite the fact that it pioneered quarantine – for the word quarantine comes from the Venetian for “40 days”, the amount of time foreign ships were impounded for in 1348. The Scuola Grande bears witness to Venice’s sufferings despite all its efforts. Tourists go there (or did) to see Tintoretto’s paintings. But when the current quarantine is over, it’s worth pausing on the staircase, where Zanchi’s gruesome scenes record the devastating plague of 1630.

Rembrandt: Portrait of Hendrickje Stoffels (c1654)

It’s a disturbing fact that some of the world’s greatest art is haunted by bubonic plague and Hendrickje Stoffels was one of its victims. She’s movingly alive in her lover Rembrandt’s portrait of her, gazing from soft dark eyes as they share total intimacy and honesty. Stoffels was the widowed Rembrandt’s housekeeper before becoming his partner in life and business. She had a daughter with him and brought up his son Titus. After he went bankrupt, she became his business representative and kept him afloat. This painting is testimony to their love. Then in 1663, a ship from Algiers brought plague to Amsterdam and she was one of its victims. Her loss contributed to the tragedy and anguish we see in Rembrandt’s late self-portraits.

Gerrit van Honthorst: Saint Sebastian (c1623)

The Roman soldier Sebastian, sentenced to be shot with arrows at close range for his Christian beliefs, was a protector saint against plague as well as a homoerotic icon. Honthorst’s painting manages to combine both elements. His native Utrecht, in the Netherlands, was hit by plague in the 1620s. This painting passionately portrays the saint as an inspiring hero of miraculous survival. Those arrows stuck deep in his flesh look as fatal as buboes – but Sebastian was nursed back to health from his ordeal. The pale skin, dark setting and intense violence of this image are inspired by Caravaggio, whose art excited Honthorst when he went to Rome.

Caravaggio: The Seven Works of Mercy (1607)

One of the most distressing results of Europe’s original pandemic and its recurrences was that the dead could not be buried decently. This was a basic “mercy” of a Christian community, as Caravaggio shows in this shadowed vision of people doing good deeds on the mean streets of Naples. A priest holds up a torch as a man is carried to burial by night, his feet peeping from his shroud. In his eyewitness account of the Black Death in Florence, Giovanni Boccaccio tells how mourning broke down and bodies were dumped in the street. “Plague pits” that have been discovered crammed with bodies confirm that the dead were dumped in mass graves.

Caterina de Julianis: Time and Death (before 1727)

Bubonic plague waned in Europe by the 18th century. Its last great ravages took place in Marseilles in 1720. This wax horror made by a nun in Naples shows how the memory persisted of an entire landscape ravaged by death. Like earlier works such as Hans Holbein’s Dance of Death prints and Bruegel the Elder’s Triumph of Death, this is a hideous vision of death as an anarchist, destroying all human hopes. It and the tradition it is part of can be traced to the Black Death itself. The memory of this pandemic has never been erased.