"I need to produce great ideas, and I believe that if I were commissioned to design a new universe, I would be mad enough to undertake it." - Giovanni Battista Piranesi

Giovanni Battista Piranesi

Mogliano Veneto, 1720

Giovanni Battista Piranesi, dit Le Piranèse, né à Mogliano Veneto, près de Trévise, appartenant alors à la République de Venise, le 10 avril 1720, baptisé le 8 novembre en l’église Saint Moïse et mort à Rome le 9 novembre 1778, est un graveur et un architecte italien.

Dans ses planches gravées Piranèse parvient à sublimer l’Antiquité. En isolant et en amplifiant les éléments architecturaux, il ajoute à ses oeuvres une dimension dramatique qui reflète son idée de la dignité et de la magnificence romaine.

Il est le fils d’Angelo, tailleur de pierre, et de Laura Lucchesi. Un frère, Angelo, l’initia au latin ainsi qu’aux bases de la littérature antique.

En 1735, il commence des études d’architecture chez son oncle Matteo Lucchesi (ingénieur) et Giovanni Antonio Scalfarotto (peintre) puis une formation de gravure à Venise chez Carlo Zucchi.

En 1740, il part pour Rome avec la suite de l’ambassadeur de Venise : Francesco Venier. Il apprend la gravure avec Fellice Polanzoni, mais surtout auprès de Giuseppe Vasi. Celui-ci lui apprend le procédé de l’eau-forte. Il apprend également la réalisation de décors de théâtre chez les frères Valeriani. Il commence aussi à cette période sa première série de planches.

En 1743, il fait paraître une première série de planches Première partie d’architecture et perspective et effectue un court voyage à Naples.

En 1744, il fait publier La Villa Royale Ambrosienne par G. Allegrini à la suite de Vues des Villas et d’autres lieux de la Toscane. Retour à Venise de mai à septembre. Ensuite, il travaille à Rome avec Carlo Nolli sur le Plan du Tibre. Parution des Diverses vues de Rome anciennes et modernes.

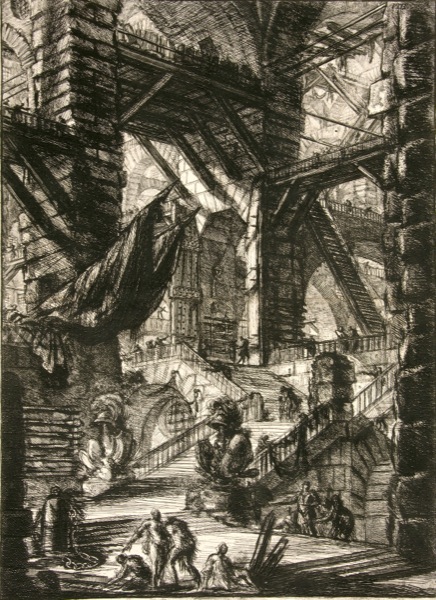

En 1745, il retourne à Venise où il commence à travailler sur les Carceri (les Prisons imaginaires). Ce sont seize univers créés lors d’un accès de fièvre. Étalage d’architecture et d’outils de constructions détournés en engins de torture, les mondes de Piranèse laissent des sensations partagées entre l’horreur et la curiosité. Le vertige, l’absence de repères connus, le côté labyrinthique en trois dimensions, renvoient à la notion d’infini, aussi traumatisante que le rapport avec l’extérieur pour celui qui est incarcéré.

En 1747, retour à Rome, via del Corso, face au siège de l’Académie de France (Palais Mancini). Il entreprend Les Vues de Rome, série qui aura une grande influence sur les architectes, peintres, sculpteurs et graveurs français de l’époque. Elle devient, pour eux, un véritable répertoire de formes. Piranèse fait une retranscription de l’Antiquité transmué par son imagination. Il utilise des cadrages particuliers, fait un gros travail de mise en scène, et exploite des contrastes violents d’ombres et de lumières. Il entreprendra aussi Les Antiquités Romaines au temps de la République.

En 1748, après un bref retour à Venise, il installe un atelier à Rome. Il publie Les Antiquités romaines au temps de la République et des premiers empereurs. Il travaille avec Giambattista Nolli au Nouveau plan de Rome.

En 1749-1750, publication de la première version des Carceri en quatorze planches (sans les numéros II et V).

En 1750, publication des Œuvres diverses d’architecture, perspective et grotesque chez Giovanni Bouchard.

En 1751, publication de la série La Magnificence de Rome.

En 1752, il épouse Angela Pasquini et publie la Récolte de diverses vues de Rome.

En 1753, publication de « Trophée de Auguste Ottaviano ».

En 1756, publication du premier des quatre volumes d’Antiquités Romaines. Il devient membre honoraire de « La Société des Antiquaires de Londres ». Publication des Lettres de justification.

En 1761, il s’installe à l’hôtel Tomati et publie la version finale des Carceri et La magnificence de l’architecture romaine. Il est nommé Académicien de Saint-Luc.

En 1762, publication de Lapides capitolini, il campo Marzio, ainsi que Description et dessin de l’émissaire du Lac d’Albano.

En 1764, publication de l’Antiquité d’Albano et du Castel Gandolfo du Pont Blackfriars, Le travail d’architecture et Récolte de quelques projets de Guernico puis les Antiquités de Cora. Il restaure, sur l’Aventin, l’église du prieuré de Malte, un de ses rares travaux d’architecte.

En 1765, publication sur les Observations sur la lettre de M. Mariette. La série Les Antiquités romaines au temps de la République est rééditée sous le titre Quelques vues d’Arc triomphal.

En 1766, il achève les travaux de restauration de l’église du prieuré de Malte.

Oneiric Architecture and Opium

https://www.theparisreview.org/blog/2014/08/15/oneiric-architecture-and-opium/

Visualizing opium dreams through the etchings of Piranesi.

What might this madness look like? Here De Quincey turns to ekphrasis, invoking Giovanni Battista Piranesi’s Carceri d’Invenzione (Imaginary Prisons), a series of etchings that depict surreal, classical-inspired dungeons:

Many years ago, when I was looking over Piranesi’s, Antiquities of Rome, Mr. Coleridge, who was standing by, described to me a set of plates by that artist, called his Dreams, and which record the scenery of his own visions during the delirium of a fever. Some of them (I describe only from memory of Mr. Coleridge’s account) represented vast Gothic halls, on the floor of which stood all sorts of engines and machinery, wheels, cables, pulleys, levers, catapults, &c. &c., expressive of enormous power put forth and resistance overcome. Creeping along the sides of the walls you perceived a staircase; and upon it, groping his way upwards, was Piranesi himself: follow the stairs a little further and you perceive it come to a sudden and abrupt termination without any balustrade, and allowing no step onwards to him who had reached the extremity except into the depths below. Whatever is to become of poor Piranesi, you suppose at least that his labours must in some way terminate here. But raise your eyes, and behold a second flight of stairs still higher, on which again Piranesi is perceived, but this time standing on the very brink of the abyss. Again elevate your eye, and a still more aerial flight of stairs is beheld, and again is poor Piranesi busy on his aspiring labours; and so on, until the unfinished stairs and Piranesi both are lost in the upper gloom of the hall. With the same power of endless growth and self-reproduction did my architecture proceed in dreams. In the early stage of my malady the splendours of my dreams were indeed chiefly architectural; and I beheld such pomp of cities and palaces as was never yet beheld by the waking eye unless in the clouds.

Completed in the mid-eighteenth century, Piranesi’s Prisons, with their vast cavernous archways and creeping staircases, remind of the impossible constructions of M. C. Escher, though Piranesi precedes Escher by nearly two hundred years. And there’s an expressiveness to Piranesi’s line, a level of permitted imprecision radically different from Escher’s mathematically inspired print work—a certain nightmarishness, even. Through the Prisons, De Quincey manages to evoke the strange, haunting infinity of his dreams. And by setting these expansive dungeons in the mind of an addict, he gets at something key about the particular creepiness of Piranesi’s constructed prisons: the crush of infinity. There’s something claustrophobic about their sheer expansiveness. The shadowy inmates of imaginary prisons, like opium eaters, are enslaved in surplus, sentenced to learn the restrictive power of excess.

Chantal McStay studies English at Columbia University and is an intern at The Paris Review.

Piranesi, Etcher Extraordinaire

Giovanni Battista Piranesi was one of the finest etchers of all time. His technical mastery rendered his strong copperplate etchings of classical antiquities brilliantly three dimensional. Piranesi combined technical perspective from his studies of architecture, archaeology, classical sculpture and mythology, with artistic flamboyance developed from his experience with Venetian theatrical stage design.

The son of a stonemason, Italian artist Giovanni Battista Piranesi (1720-1778) was born near Venice, and was introduced to the Latin language and ancient civilizations by his brother who was a Carthusian monk. He received practical training in structural and hydraulic engineering from his maternal uncle Matteo Lucchesi, who as Magistrato delle Acque of the Venetian waterworks, was an engineer specializing in excavation and drainage.

Piranesi the architect.

By the age of 20 Piranesi was in Rome on the staff of the Venetian ambassador, Marco Foscarini. Inspired by the grand architecture of imperial Rome, Giovanni Battista aspired to become an architect, but had difficulty securing commissions in this field. His only important architectural work came much later, between 1764 and 1766, when he designed and restored the monastery church of the Priory of the Knights of Malta, Santa Maria del Priorato on the Aventine Hill in Rome, and also built the piazza in front of the church. Piranesi’s fine stonemasonry incorporated appropriate heraldry, military and naval references, as well as motifs from ancient Rome and Etruria. The pièce de résistance was his elaborately sculpted main altar.

Venetian Pope Clement XIII recognized Piranesi’s contribution to the glory of the church, and in 1765 conferred upon him the Papal Order of Chivalry known as the Order of the Golden Spur (or Order of the Golden Militia). This Papal Order of Chivalry granted him the right to sign his work Cav. G.B. Piranesi or Cavaliere Gio. Batta. Piranesi.

Piranesi the architect.

By the age of 20 Piranesi was in Rome on the staff of the Venetian ambassador, Marco Foscarini. Inspired by the grand architecture of imperial Rome, Giovanni Battista aspired to become an architect, but had difficulty securing commissions in this field. His only important architectural work came much later, between 1764 and 1766, when he designed and restored the monastery church of the Priory of the Knights of Malta, Santa Maria del Priorato on the Aventine Hill in Rome, and also built the piazza in front of the church. Piranesi’s fine stonemasonry incorporated appropriate heraldry, military and naval references, as well as motifs from ancient Rome and Etruria. The pièce de résistance was his elaborately sculpted main altar.

Venetian Pope Clement XIII recognized Piranesi’s contribution to the glory of the church, and in 1765 conferred upon him the Papal Order of Chivalry known as the Order of the Golden Spur (or Order of the Golden Militia). This Papal Order of Chivalry granted him the right to sign his work Cav. G.B. Piranesi or Cavaliere Gio. Batta. Piranesi.

Architect or Artist?

Architect or Artist?In Venice most of the time between 1743 and 1747, Giambattista returned to central Rome and set up his own workshop on Via del Corso, where he began creating his series of large etchings of Vedute di Roma (Views of Rome). Piranesi meticulously measured and recorded ancient Roman buildings, aqueducts, and archaeological sites. He then drew and etched them onto copper in his own distinctive style, resulting in Piranesi being considered by many to be the first great artist of Romanticism. This series of etchings brought him not only fame, but also his election as honorary Fellow of the Society of Antiquaries in London in 1757. Piranesi continued to produce his dramatic plates for this series until the year he died.

In 1761 Giovanni Battista Piranesi joined the Rome Academy of Saint Luke, Accademia di San Luca, an association of artists, which included painters, sculptors and architects. The Academy’s purpose was to elevate the status of all artists above that of 'mere craftsmen'. Piranesi set up his own printing facility and published his own etchings for Delle magnificenze ed architettura de Romani (The magnificence of Roman architecture), which he used to support the Italian point of view that Roman art had derived from the Etruscans not the Greeks (as had been the opinion of French and British scholars of the day).

Stonemason and Etcher.

At his workshop, Piranesi not only creatively restored Roman archaeological discoveries, he also designed and built amazing artefacts in stone, combining fantastical themes with his recordings of discovered antiquities. As wealthy Europeans travelled to Rome, they commissioned stonemasonry from the Piranesi workshop. Exquisite Piranesi etchings of this work are still enjoyed today. Piranesi was not only fascinated by Roman antiquities, his designs also reflected Baroque and Rococo style, earlier Etruscan, Greek and Egyptian design, and mythological symbolism.

As his father had done, Giovanni Battista taught his craft to his children. He instructed his sons Francesco and Pietro, and his daughter Laura, in etching, engraving and architectural principles, but only Francesco excelled.

Piranesi Vases and Urns.

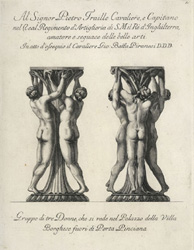

Francesco Piranesi (1758-1810), assisted his father in his prosperous business, and in the imaginative restoration and creation of ornamental antiquities – in particular of the urns and pedestals for which Piranesi gained international renown. Francesco assisted his father in some etchings for Vasi, Candelabri, Cippi y Sarcofagi Tripodi Lucerne ed Ornamenti Antichi disegnati ed incise dal Cav. Gio. Batt. Piranesi (Vases, Candelabri, Gravestone Pillars and Sarcofagi, Tripods, Lamps and Antique Ornaments designed and etched by Cavalier Giovanni Battista Piranesi) – Piranesi’s best known work of Roman antiquities. They were first issued as individual etchings published in Rome between 1773 and 1778.

Piranesi judiciously dedicated many of these plates to clients who had commissioned them, and he inscribed some plates with information about the original discovery and the present location of the antiquities. Piranesi's consumate skill as an etcher is shown in his vases.

Piranesi's bold inventiveness, extraordinary imagination, and masterful graphic technique established a new benchmark in 18th century printmaking. The light and shade of Piranesi’s etchings show wonderful depth, particularly in illustrating his relief carvings, with a clarity of line that is quite rare, even in the finest of early engravers’ and etchers’ work.

Piranesi Vases have been avidly collected since their creation over 300 years ago. Such has been their popularity, that reproductions are now available of some of his wonderful vases.

Original etchings are available on this website at Antique Prints/Classical-Design.

Heritage Editions reproductions images that were produced from a few of the rare original etchings are also available on this website at

Piranesi Vases and Urns.

Francesco Piranesi (1758-1810), assisted his father in his prosperous business, and in the imaginative restoration and creation of ornamental antiquities – in particular of the urns and pedestals for which Piranesi gained international renown. Francesco assisted his father in some etchings for Vasi, Candelabri, Cippi y Sarcofagi Tripodi Lucerne ed Ornamenti Antichi disegnati ed incise dal Cav. Gio. Batt. Piranesi (Vases, Candelabri, Gravestone Pillars and Sarcofagi, Tripods, Lamps and Antique Ornaments designed and etched by Cavalier Giovanni Battista Piranesi) – Piranesi’s best known work of Roman antiquities. They were first issued as individual etchings published in Rome between 1773 and 1778.

Piranesi judiciously dedicated many of these plates to clients who had commissioned them, and he inscribed some plates with information about the original discovery and the present location of the antiquities. Piranesi's consumate skill as an etcher is shown in his vases.

Piranesi's bold inventiveness, extraordinary imagination, and masterful graphic technique established a new benchmark in 18th century printmaking. The light and shade of Piranesi’s etchings show wonderful depth, particularly in illustrating his relief carvings, with a clarity of line that is quite rare, even in the finest of early engravers’ and etchers’ work.

Piranesi Vases have been avidly collected since their creation over 300 years ago. Such has been their popularity, that reproductions are now available of some of his wonderful vases.

Original etchings are available on this website at Antique Prints/Classical-Design.

Heritage Editions reproductions images that were produced from a few of the rare original etchings are also available on this website at

Voyage to the center of Piranesi’s imaginary prison

Giovanni Battista Piranesi, the son of stonemason and nephew of an engineer, first trained under that uncle as an architect maintaining the intricate waterworks of his native Venice. Even though he only ever got one job as an architect in his all too short life, he never lost the passion for buildings. It was as an artist that he made his name. He learned etching in Rome and combined his artistic talent with his favorite subject matter to create views of the city that became popular among Grand Tourists. Piranesi’s etchings of ancient Roman architecture were not only captured with the meticulous understanding of the builder, but were drawn with such powerful chiaroscuro dynamism that Goethe, for one, who first came to know the city through Piranesi’s books, was actually disappointed when he saw the real thing.

Giovanni Battista Piranesi, the son of stonemason and nephew of an engineer, first trained under that uncle as an architect maintaining the intricate waterworks of his native Venice. Even though he only ever got one job as an architect in his all too short life, he never lost the passion for buildings. It was as an artist that he made his name. He learned etching in Rome and combined his artistic talent with his favorite subject matter to create views of the city that became popular among Grand Tourists. Piranesi’s etchings of ancient Roman architecture were not only captured with the meticulous understanding of the builder, but were drawn with such powerful chiaroscuro dynamism that Goethe, for one, who first came to know the city through Piranesi’s books, was actually disappointed when he saw the real thing. Piranesi didn’t limit himself to depictions of Rome and its ruins for the pilgrims and tourists. In 1745, he began work on an entirely new vision, combining his artistic style and understanding of ancient monumental construction to create a unique group of etchings called Carceri d’Invenzione (Imaginary Prisons). The imaginary part is that they bear no relation to any actual prisons of the era which were mostly cramped dungeon cells in the towers and palaces of the Church and aristocracy. Piranesi’s invented prisons were cavernous labyrinths peppered with intimidatingly suggestive mechanisms where human figures are barely present and dwarfed by their surroundings.

Piranesi didn’t limit himself to depictions of Rome and its ruins for the pilgrims and tourists. In 1745, he began work on an entirely new vision, combining his artistic style and understanding of ancient monumental construction to create a unique group of etchings called Carceri d’Invenzione (Imaginary Prisons). The imaginary part is that they bear no relation to any actual prisons of the era which were mostly cramped dungeon cells in the towers and palaces of the Church and aristocracy. Piranesi’s invented prisons were cavernous labyrinths peppered with intimidatingly suggestive mechanisms where human figures are barely present and dwarfed by their surroundings. The first edition of Carceri d’Invenzione was published in 1750. It was a collection of 14 untitled etchings drawn in a rough sketch-like style. You can see all 14 of the original Carceri in order here. Ten years later, he would return to his imaginary prisons and do a major revamp of the etchings. He added two new ones and fleshed out the others with even more complex architectural features, increased contrasts of shadow and light, arches, staircases and vaults that lead nowhere.

The first edition of Carceri d’Invenzione was published in 1750. It was a collection of 14 untitled etchings drawn in a rough sketch-like style. You can see all 14 of the original Carceri in order here. Ten years later, he would return to his imaginary prisons and do a major revamp of the etchings. He added two new ones and fleshed out the others with even more complex architectural features, increased contrasts of shadow and light, arches, staircases and vaults that lead nowhere. The prison etchings were part of an artistic tradition called the capriccio, a fantasy aggregation of structures and art works that doesn’t exist in real life. These sorts of imaginary viewpoints were popular with tourists because they compressed the “must see” ruins and artworks into one painting. What Piranesi did with the form, however, was entirely new. The prisons were expressions of visions in his mind, not of tourist bullet points. They wouldn’t be purchased as pre-photography postcards, but the prisons’ tenebrous atmosphere and emotional impact were highly influential for the Romantics of the late 18th/early 19th centuries. The irrational elements like infinitely regressing passageways would later inspire the Surrealists and if Escher’s Relativity doesn’t owe Piranesi a huge debt, I’ll be a monkey’s uncle.

The prison etchings were part of an artistic tradition called the capriccio, a fantasy aggregation of structures and art works that doesn’t exist in real life. These sorts of imaginary viewpoints were popular with tourists because they compressed the “must see” ruins and artworks into one painting. What Piranesi did with the form, however, was entirely new. The prisons were expressions of visions in his mind, not of tourist bullet points. They wouldn’t be purchased as pre-photography postcards, but the prisons’ tenebrous atmosphere and emotional impact were highly influential for the Romantics of the late 18th/early 19th centuries. The irrational elements like infinitely regressing passageways would later inspire the Surrealists and if Escher’s Relativity doesn’t owe Piranesi a huge debt, I’ll be a monkey’s uncle. In 2010, the Sale del Convitto in Venice held an exhibition Le Arti di Piranesi: architetto, incisore, antiquario, vedutista, designer (The Arts of Piranesi: architect, engraver, antiquarian, vedutista, designer) to coincide with the Venice Biennale of Architecture. The Carceri etchings played a central part in the show, and graphic artist Gregoire Dupond of Factum Arte brought them to virtual life with an absolutely riveting animation. He took the 16 prints of the second edition and transformed them into a three-dimensional space so viewers can travel deep into Piranesi’s imagination.

In 2010, the Sale del Convitto in Venice held an exhibition Le Arti di Piranesi: architetto, incisore, antiquario, vedutista, designer (The Arts of Piranesi: architect, engraver, antiquarian, vedutista, designer) to coincide with the Venice Biennale of Architecture. The Carceri etchings played a central part in the show, and graphic artist Gregoire Dupond of Factum Arte brought them to virtual life with an absolutely riveting animation. He took the 16 prints of the second edition and transformed them into a three-dimensional space so viewers can travel deep into Piranesi’s imagination.

It’s 12 minutes long and it’s nothing short of riveting.

Gravures de Piranese

La BIU Lsh possède sept volumes de gravures de Piranèse, imprimées à Rome du vivant de l’artiste. Il s’agit pour plusieurs d’entre elles d’éditions princeps que l’on retrouve assez peu dans les collections françaises. Dans ces recueils affleurent l’intérêt de Piranèse pour l’architecture pure et son goût pour les vestiges antiques auxquels il donne des proportions démesurées.

La notion d’échelle disparaît dans cette image. On a du mal à se figurer la taille réelle des objets mis en scène. Le spectateur ne sait plus s’il se trouve écrasé face à un vase colossal ornés de bibelots et d’ossements ou s’il a sous les yeux une vue grossie d’un détail pittoresque.

Venu de Venise à Rome pour se former, Piranèse se détache très rapidement de ses maîtres et impose son propre style sombre et tourmenté loin des « vedutisti », les habituelles vues de ville. Il participe à la réhabilitation de l’Antiquité propre au XVIIIe siècle et cherche en même temps à s’en détacher. Il dessine le passé et le transcende en produisant de véritables « fictions architecturales ». Les bâtiments qu’il couche sur le papier n’existent pas tels quels, il les réinvente comme d’inquiétants décors de théâtre, dans lesquels prennent place de curieux personnages issus de la Commedia dell’arte.

Des personnages obscurs aux silhouettes effilées prennent place dans le décor immense et instable de fortifications en ruines. Grâce à ces êtres presque difformes, Piranèse joue sur les contrastes de proportions et accentue l’ambiance de fin du monde qui règne dans le décor sinistre en même temps qu’il lui donne vie.

Grâce à la technique de l’eau-forte, il sature l’image, joue sur les proportions, les effets de clair-obscur et fait pénétrer l’architecture dans le domainedu fantastique. Piranèse mêle les références à l’art égyptien ou étrusque, donnant ainsi à son travail une résonance archéologique, également inspirée par d’importants travaux de fouilles dans la région de Rome. Cette multiplicité d’inspirations, loin d’un retour idéalisé vers l’Antiquité, place Piranèse en précurseur du courant éclectique. S’il insuffle ainsi les prémices du romantisme, notamment avec ses Prisons, dont la BIU possède une planche, Piranèse alimente des querelles avec nombres d’artistes en affirmant la supériorité de l’Antiquité romaine sur l’Antiquité grecque. Pierre-Jean Mariette, auteur du recueil Crozat, sera l’un des ses principaux détracteurs.

Le plan qui se corne, l’ombre qui passe à travers les colonnes du temple, les figurants dont on ne sait pas s’ils sont des statues ou des êtres de chair et la précision de mesures, des légendes, forment autant de détails qui démontrent l’habileté de Piranèse à mêler architecture pure, dessin et archéologie.

Bibliographie :

- FOCILLON, Henri. Giovanni-Battista Piranesi : 1720 – 1778. Paris : H. Jansen, 1918, rééd. Paris : In Folio Ed., 2001.

- KELLER, Luzius. Piranèse et les romantiques français : le mythe des escaliers en spirale. Paris : J. Corti, 1966.