Baroque art in Europe, an introduction

Gian Lorenzo Bernini; View to Cathedra Petri (Chair of St. Peter), gilded bronze, gold, wood, stained glass; 1647-53 (apse of Saint Peter's Basilica, Vatican City, Rome). Image credit: Steven Zucker, CC BY-NC-SA 2.0

Rome: from the whore of Babylon to the resplendent bride of Christ

When Martin Luther tacked his 95 theses to the doors of Wittenberg Cathedral in 1517 protesting the Catholic Church’s corruption, he initiated a movement that would transform the religious, political, and artistic landscape of Europe. For the next century, Europe would be in turmoil as new political and religious boundaries were determined, often through bloody military conflicts. Only in 1648, with the signing of the Treaty of Westphalia, did the conflicts between Protestants and Catholics subside in continental Europe.

Martin Luther focused his critique on what he saw as the Church’s greed and abuse of power. He called Rome, the seat of papal power, “the whore of Babylon” decked out in finery of expensive art, grand architecture, and sumptuous banquets. The Church responded to the crisis in two ways: by internally addressing issues of corruption and by defending the doctrines rejected by the Protestants. Thus, while the first two decades of the 16th century were a period of lavish spending for the Papacy, the middle decades were a period of austerity. As one visitor to Rome noted in the 1560s, the entire city had become a convent. Piety and asceticism ruled the day.

By the end of the 16th century, the Catholic Church was once again feeling optimistic, even triumphant. It had emerged from the crisis with renewed vigor and clarity of purpose. Shepherding the faithful—instructing them on Catholic doctrines and inspiring virtuous behavior—took center stage. Keen to rebuild Rome’s reputation as a holy city, the Papacy embarked on extensive building and decoration campaigns aimed at highlighting its ancient origins, its beliefs, and its divinely-sanctioned authority. In the eyes of faithful Catholics, Rome was not an unfaithful whore, but a pure bride, beautifully adorned for her union with her divine spouse.

The art of persuasion: instruct, delight, move

While the Protestants harshly criticized the cult of images, the Catholic Church ardently embraced the religious power of art. The visual arts, the Church argued, played a key role in guiding the faithful. They were certainly as important as the written and spoken word, and perhaps even more important since they were accessible to the learned and the unlearned alike. In order to be effective in its pastoral role, religious art had to be clear, persuasive, and powerful. Not only did it have to instruct, it had to inspire. It had to move the faithful to feel the reality of Christ’s sacrifice, the suffering of the martyrs, the visions of the saints.

Caravaggio, The Crowning with Thorns, 1602-04, oil on canvas, 165.5 x 127 cm (Kunsthistorisches Museum, Vienna)

The Church’s emphasis on art’s pastoral role prompted artists to experiment with new and more direct means of engaging the viewer. Artists like Caravaggio turned to a powerful and dramatic realism, accentuated by bold contrasts of light and dark, and tightly-cropped compositions that enhanced the physical and emotional immediacy of the depicted narrative.

Other artists, like Annibale Carracci—who also experimented with realism—ultimately settled on a more classical visual language, inspired by the vibrant palette, idealized forms, and balanced compositions of the High Renaissance, see image above. Still others, like Giovanni Battista Gaulli, turned to daring feats of illusionism that blurred not only the boundaries between painting, sculpture, and architecture, but also those between the real and depicted worlds. In so doing, the divine was made physically present and palpable. Whether through shocking realism, dynamic movement, or exuberant ornamentation, 17th-century art was meant to impress. It aimed to convince the viewer of the truth of its message by impacting the senses, awakening the emotions, and activating—even sharing—the viewer’s space.

Giovanni Battista Gaulli, also known as il Baciccio,The Triumph of the Name of Jesus, Il, Gesù ceiling fresco, 1672-1685

The Catholic monarchs and their territories

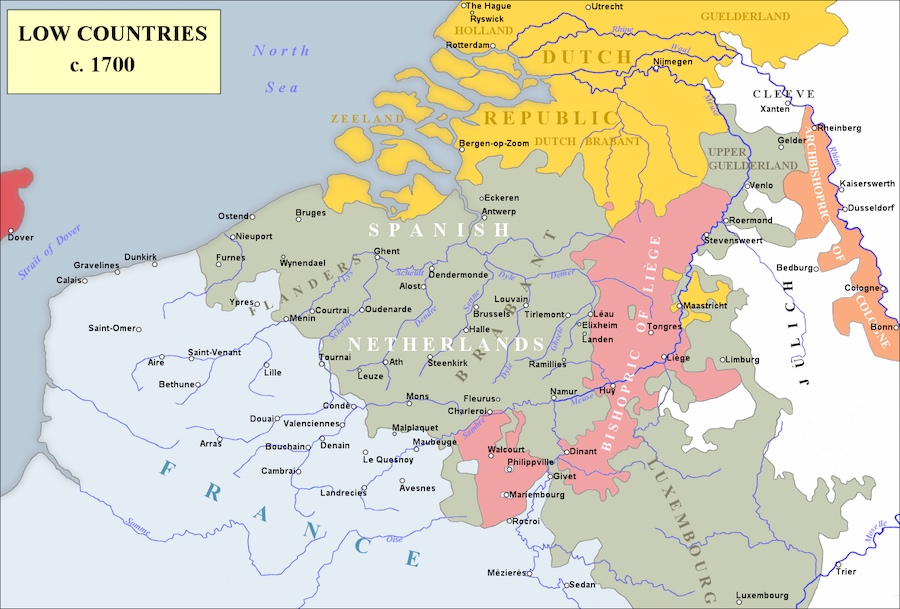

The monarchs of Spain, Portugal, and France also embraced the more ornate elements of 17th-century art to celebrate Catholicism. In Spain and its colonies, rulers invested vast resources on elaborate church facades, stunning, gold-covered chapels and tabernacles, and strikingly-realistic polychrome sculpture. In the Spanish Netherlands, where sacred art had suffered terribly as a result of the Protestant iconoclasm—the destruction of art—civic and religious leaders prioritized the adornment of churches as the region reclaimed its Catholic identity. Refurnishing the altars of Antwerp’s churches kept Peter Paul Rubens’ workshop busy for many years. Europe’s monarchs also adopted this artistic vocabulary to proclaim their own power and status. Louis XIV, for example, commissioned the splendid buildings and gardens of Versailles as a visual expression of his divine right to rule.

Peter Paul Rubens, Elevation of the Cross, 1610, oil on wood, 15 ft 1-7/8 in x 11 ft 1-1/2 in (originally for Saint Walpurgis, Antwerp [destroyed], now in Antwerp Cathedral)

The Protestant north

In the Protestant countries, and especially in the newly-independent Dutch Republic, modern-day Holland, the artistic climate changed radically in the aftermath of the Reformation. Two of the wealthiest sources of patronage—the monarchy and the Church—were now gone. In their stead arose an increasingly prosperous middle class eager to express its status and its new sense of national pride through the purchase of art.

By the middle of the 17th century, a new market had emerged to meet the artistic tastes of this class. The demand was now for smaller-scale paintings suitable for display in private homes. These paintings included religious subjects for private contemplation, as seen in Rembrandt’s poignant paintings and prints of biblical narratives, as well as portraits documenting individual likenesses.

Judith Leyster, Self-Portrait, c. 1630, oil on canvas, 651 x 746 cm (National Gallery of Art, Washington) But, the greatest change in the market was the dramatic increase in the popularity of landscapes, still-lifes, and scenes of everyday life—known as genre painting. Indeed, the proliferation of these subjects as independent artistic genres was one of the 17th century’s most significant contributions to the history of Western art.

In all of these genres, artists revealed a keen interest in replicating observed reality—whether it be the light on the Dutch landscape, the momentary expression on a face, or the varied textures and materials of the objects the Dutch collected as they reaped the benefits of their expanding mercantile empire. These works demonstrated as much artistic virtuosity and physical immediacy as the grand decorations of the palaces and churches of Catholic Europe.

In the context of European history, the period from c. 1585 to c. 1700/1730 is often called the Baroque era. The word baroque derives from the Portuguese and Spanish words for a large, irregularly-shaped pearl—barroco and barrueco, respectively. Eighteenth-century critics were the first to apply the term to the art of the 17th century. It was not a term of praise. To the eyes of these critics, who favored the restraint and order of Neoclassicism, the works of Bernini, Borromini, and Pietro da Cortona appeared bizarre, absurd, even diseased—in other words, misshapen, like an imperfect pearl.

Francisco de Zurbarán, Saint Francis of Assisi According to Pope Nicholas V's Vision, c. 1640, oil on canvas, 110.5 x 180.5 cm (Museum Nacional d'Art de Catalunya, Barcelona) Baroque—the word, the style, the period

Baroque—the word, the style, the period

By the middle of the 19th century, the word baroque had lost its pejorative implications and was used to describe the ornate and complex qualities present in many examples of 17th-century art, music, and literature. Eventually, the term came to designate the historical period as a whole.

In the context of painting, for example, the stark realism of Zurbaran’s altarpieces, the quiet intimacy of Vermeer’s domestic interiors, and the restrained classicism of Poussin’s landscapes are all Baroque—now with a capital B to indicate the historical period—regardless of the absence of the stylistic traits originally associated with the term.

Scholars continue to debate the validity of this label, admitting the usefulness of having a label for this distinct historical period, while also acknowledging its limitations in characterizing the variety of artistic styles present in the 17th century.

Essay by Dr. Esperança Camara

Additional resources