ALBRECHT DURER’S “THE KNIGHT, DEATH, AND THE DEVIL”

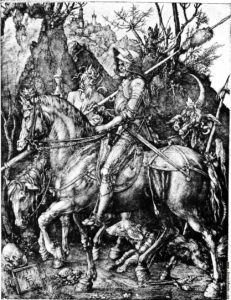

Dürer's Knight, Death, and the Devil is one of three large prints of 1513–14 known as his Meisterstiche (master engravings). The other two are Melancholia I and Saint Jerome in His Study. Though not a trilogy in the strict sense, the prints are closely interrelated and complementary, corresponding to the three kinds of virtue in medieval scholasticism—theological, intellectual, and moral. Called simply the Reuter (Rider) by Dürer, Knight, Death, and the Devil embodies the state of moral virtue. The artist may have based his depiction of the "Christian Knight" on an address from Erasmus's Instructions for the Christian Soldier (Enchiridion militis Christiani), published in 1504: "In order that you may not be deterred from the path of virtue because it seems rough and dreary ... and because you must constantly fight three unfair enemies—the flesh, the devil, and the world—this third rule shall be proposed to you: all of those spooks and phantoms which come upon you as if you were in the very gorges of Hades must be deemed for naught after the example of Virgil's Aeneas ... Look not behind thee." Riding steadfastly through a dark Nordic gorge, Dürer's knight rides past Death on a Pale Horse, who holds out an hourglass as a reminder of life's brevity, and is followed closely behind by a pig-snouted Devil. As the embodiment of moral virtue, the rider—modeled on the tradition of heroic equestrian portraits with which Dürer was familiar from Italy—is undistracted and true to his mission. A haunting expression of the vita activa, or active life, the print is a testament to the way in which Dürer's thought and technique coalesced brilliantly in the "master engravings."

DESCRIPTION

In the 1500s, artists celebrated male figures whose fortitude and faith enabled them to resist temptation. Dürer's Knight, Death, and the Devil, one of the artist's three master works, references the active life of man, celebrated in the soldier on his noble horse. Resolutely forging ahead through the dark gorge, he ignores the horned devil and manifestations of evil that cross his path. Even confronted by Death itself, crowned with snakes and holding the hourglass of mortality, the soldier, with his faithful dog, represents the righteousness needed to steel oneself against wickedness.

In the 1500s, artists celebrated male figures whose fortitude and faith enabled them to resist temptation. Dürer's Knight, Death, and the Devil, one of the artist's three master works, references the active life of man, celebrated in the soldier on his noble horse. Resolutely forging ahead through the dark gorge, he ignores the horned devil and manifestations of evil that cross his path. Even confronted by Death itself, crowned with snakes and holding the hourglass of mortality, the soldier, with his faithful dog, represents the righteousness needed to steel oneself against wickedness.

Knight, Death and the Devil

Albrecht Durer’s, The Knight, Death, and the Devil is a copper engraving created in 1513. It is one of three master prints of Durer. Durer was a German from Nuremberg with an art background that included painting, printmaking and engraving. Durer’s engraving was inspired by the church reformer Erasmus of Rotterdam; Erasmus’s Enchiridion Militis Christiani. According to Weislogel, there are letters as evidence that he was inspired by Erasmus work. This engraving from the renaissance intrigued me so much by all the symbolism associated with it. Each part of the engraving means something and creates a larger understanding of the engraving itself. When looking at it you can always find something new and creates a story behind the engraving because there is so much detail. When doing some research I learned about a castle above the forest and how that could be depicted as the final destination for the knight. When first viewing the engraving I didn’t notice it at all and reading about it on The British Museum made a lot more sense. These connection in a piece of art are interesting to me and make the painting more enjoyable to look at.

The engraving holds a lot of iconography throughout the entire painting. The horsemen in the center of the picture is considered a “knight of christ” or a “good christian soldier”. The knight is traveling to the kingdom of light (pictured above the forest) and is currently traveling through the forest of darkness where he meets death. The knight does not travel alone as he is “accompanied by his faithful dog” which represents loyalty (4RealArts). Death is symbolized a couple of ways in the engraving. The first to notice would have to be the man in the background with serpent hair, he “holds a hourglass up to the knight as a reminder that his time on earth is limited” (Slade). The next character to notice would be the devil that is represented as a single horned goat. A skull also lays on the ground reminding the knight that death is the fate of all mankind. The knight does not acknowledge any of these signs of death and rides on. There is also a lizard below the tail end of the horse representing evil in christianity.

The meaning of this work has a few different interpretations. The general interpretation and the one that I agree most with is that the engraving is a celebration of the knight’s Christian faith and ideals of humanism. This engraving is a work of I believe is Protestant Reformation as it uses iconography to show the artists ideals. I would also back this by saying it takes a hostile approach in the depiction of death as there are three representations constantly reminding the knight. Some of the other interpretations include Thausing’s sanguinity representation and Karling’s depiction of the knight as a robber baron due to the fox tail around the weapon representing greed.

References

References

Slade, Felix. “Albrecht Dürer, Knight, Death and the Devil, a Copperplate Engraving.” The British Museum. N.p., n.d. Web. https://www.britishmuseum.org/explore/highlights/highlight_objects/pd/a/d%C3%BCrer_knight,_death_and_devil.aspx

Weislogel, Andrew C. “Albrecht Dürer: The Master Prints.” Johnson Museum of Art. N.p., Dec. 2005. Web. 9 June 2014.http://museum.cornell.edu/exhibitions/albrecht-durer-the-master-prints.html

“The Northern Renaissance.” The Northern Renaissance. N.p., n.d. Web. 9 June 2014. http://robinurton.com/history/Renaissance/northrenaiss.htm

=========================================================

by Deac. Carolyn Brinkley

Who is the Rider? Although Albrecht Dürer’s “Knight, Death, and the Devil” has been acclaimed as one of Europe’s greatest masterwork engravings since its publication in 1513, it has also been one of the most provocative pieces of art in the past 500 years. All agree that the copper engraving is technically stunning, but the interpretation of the Rider has been and continues to be greatly debated. Some say it depicts the virtuous soldier in Erasmus of Rotterdam’s 1504 Handbook of the Christian Soldier. Other diverse opinions for the identity of the Knight over the centuries are: an allegory of human strength and courage, a servant of Dürer’s patron, St. George, Luther, Pope Julius II, Savonarola, and strangely, a robber baron in league with death and the devil against the peasants. During the Nazi period the identity of the Rider was even ascribed to Adolf Hitler when the city of Nuremberg presented him with an original copy of “Knight, Death, and the Devil.”

Who is the Rider? Although Albrecht Dürer’s “Knight, Death, and the Devil” has been acclaimed as one of Europe’s greatest masterwork engravings since its publication in 1513, it has also been one of the most provocative pieces of art in the past 500 years. All agree that the copper engraving is technically stunning, but the interpretation of the Rider has been and continues to be greatly debated. Some say it depicts the virtuous soldier in Erasmus of Rotterdam’s 1504 Handbook of the Christian Soldier. Other diverse opinions for the identity of the Knight over the centuries are: an allegory of human strength and courage, a servant of Dürer’s patron, St. George, Luther, Pope Julius II, Savonarola, and strangely, a robber baron in league with death and the devil against the peasants. During the Nazi period the identity of the Rider was even ascribed to Adolf Hitler when the city of Nuremberg presented him with an original copy of “Knight, Death, and the Devil.”

Who is the Rider? Dürer’s title for his engraving was simply, “Der Reuter” which means “The Rider.” Perhaps this is an indication that for Dürer, the Knight, rather than the surrounding elements of evil, was the focus. A short excursus into the artist’s great suffering during 1513-1514 may shed some light. Dürer’s work on the engraving corresponds to the exact time period that his beloved mother, Barbara, suddenly became deathly ill, lingering an entire year. She was lovingly cared for in his household. At the time of her death, Albrecht journals of his mother, “Her most frequent habit was to go much to the church. She always upbraided me well if I did not do right, and she was ever in great anxiety about my sins and those of my brother. And if I went out or in, her saying was always, ‘Go in the name of Christ.’ She constantly gave us holy admonitions with deep earnestness and she always had great thought for our soul’s health. I cannot enough praise her good works and the compassion she showed to all, as well as her high character.” [1] Surely witnessing his mother’s faith and piety had a profound influence on Dürer’s work especially during her extended suffering as she journeyed Heavenward.

Who is the Rider? Dürer employed a method of signing his artwork that gives the viewer a vignette commentary on his interpretation. Not only does his distinctive AD monogram say something about the artist due to its location, but it gives Dürer himself an ongoing visual presence in his work. In “Knight, Death and the Devil”, the lower left corner is of utmost significance in understanding the scene. In Renaissance iconography the skull represents Adam and mankind’s sin. It rests on a stump picturing the  prophecy of the Second Adam: “There shall come forth a shoot from the stump of Jesse.” (Is. 11:1) Leaning directly in front is Dürer’s signature placard with his monogram, date of 1513, and the letter “S”, thought to be the Latin abbreviation for “Salus” meaning safety and salvation. This corner trio sets the tone for the entire engraving. Victory is already a foregone conclusion. The horse and Rider magnificently fill the entire woodcut. All else pales and has no power. The decaying corpse of death threatening with the hourglass of time and the ridiculous devil monster brandishing his spear can do no harm. Living oak leaves, icon for the resurrected Christ, adorn the head and tail of the resolutely striding horse. Fully arrayed and protected with the armor of God, the Rider looks neither left nor right nor behind, but only ahead as he confidently and steadfastly journeys onward to the Holy City. “Therefore, take up the whole armor of God, that you may be able to withstand in the evil day, and having done all, to stand firm.” (Eph. 6:13)

prophecy of the Second Adam: “There shall come forth a shoot from the stump of Jesse.” (Is. 11:1) Leaning directly in front is Dürer’s signature placard with his monogram, date of 1513, and the letter “S”, thought to be the Latin abbreviation for “Salus” meaning safety and salvation. This corner trio sets the tone for the entire engraving. Victory is already a foregone conclusion. The horse and Rider magnificently fill the entire woodcut. All else pales and has no power. The decaying corpse of death threatening with the hourglass of time and the ridiculous devil monster brandishing his spear can do no harm. Living oak leaves, icon for the resurrected Christ, adorn the head and tail of the resolutely striding horse. Fully arrayed and protected with the armor of God, the Rider looks neither left nor right nor behind, but only ahead as he confidently and steadfastly journeys onward to the Holy City. “Therefore, take up the whole armor of God, that you may be able to withstand in the evil day, and having done all, to stand firm.” (Eph. 6:13)

prophecy of the Second Adam: “There shall come forth a shoot from the stump of Jesse.” (Is. 11:1) Leaning directly in front is Dürer’s signature placard with his monogram, date of 1513, and the letter “S”, thought to be the Latin abbreviation for “Salus” meaning safety and salvation. This corner trio sets the tone for the entire engraving. Victory is already a foregone conclusion. The horse and Rider magnificently fill the entire woodcut. All else pales and has no power. The decaying corpse of death threatening with the hourglass of time and the ridiculous devil monster brandishing his spear can do no harm. Living oak leaves, icon for the resurrected Christ, adorn the head and tail of the resolutely striding horse. Fully arrayed and protected with the armor of God, the Rider looks neither left nor right nor behind, but only ahead as he confidently and steadfastly journeys onward to the Holy City. “Therefore, take up the whole armor of God, that you may be able to withstand in the evil day, and having done all, to stand firm.” (Eph. 6:13)

prophecy of the Second Adam: “There shall come forth a shoot from the stump of Jesse.” (Is. 11:1) Leaning directly in front is Dürer’s signature placard with his monogram, date of 1513, and the letter “S”, thought to be the Latin abbreviation for “Salus” meaning safety and salvation. This corner trio sets the tone for the entire engraving. Victory is already a foregone conclusion. The horse and Rider magnificently fill the entire woodcut. All else pales and has no power. The decaying corpse of death threatening with the hourglass of time and the ridiculous devil monster brandishing his spear can do no harm. Living oak leaves, icon for the resurrected Christ, adorn the head and tail of the resolutely striding horse. Fully arrayed and protected with the armor of God, the Rider looks neither left nor right nor behind, but only ahead as he confidently and steadfastly journeys onward to the Holy City. “Therefore, take up the whole armor of God, that you may be able to withstand in the evil day, and having done all, to stand firm.” (Eph. 6:13) Who is the Rider? It is you, dear Christian! “Go in the name of Christ!”[2]

Who is the Rider? It is you, dear Christian! “Go in the name of Christ!”[2]

Deaconess Carolyn S. Brinkley is the Director of the Military Project at Concordia Theological Seminary, Fort Wayne, Indiana

[1] William Martin Conway, Tr. and Ed. The Writings of Albrecht Dürer, (New York :Philosophical Library, 1958),78.

==========================

Albrecht Dürer, The Knight, Death and the Devil

Albrecht Dürer, The Knight, Death and the Devil (Der Reuter)

| Engraving, 24.2 x 18.4 cm, Baillieu Library Collection, The University of Melbourne, Accession No. : 1988.2014.000.000. |

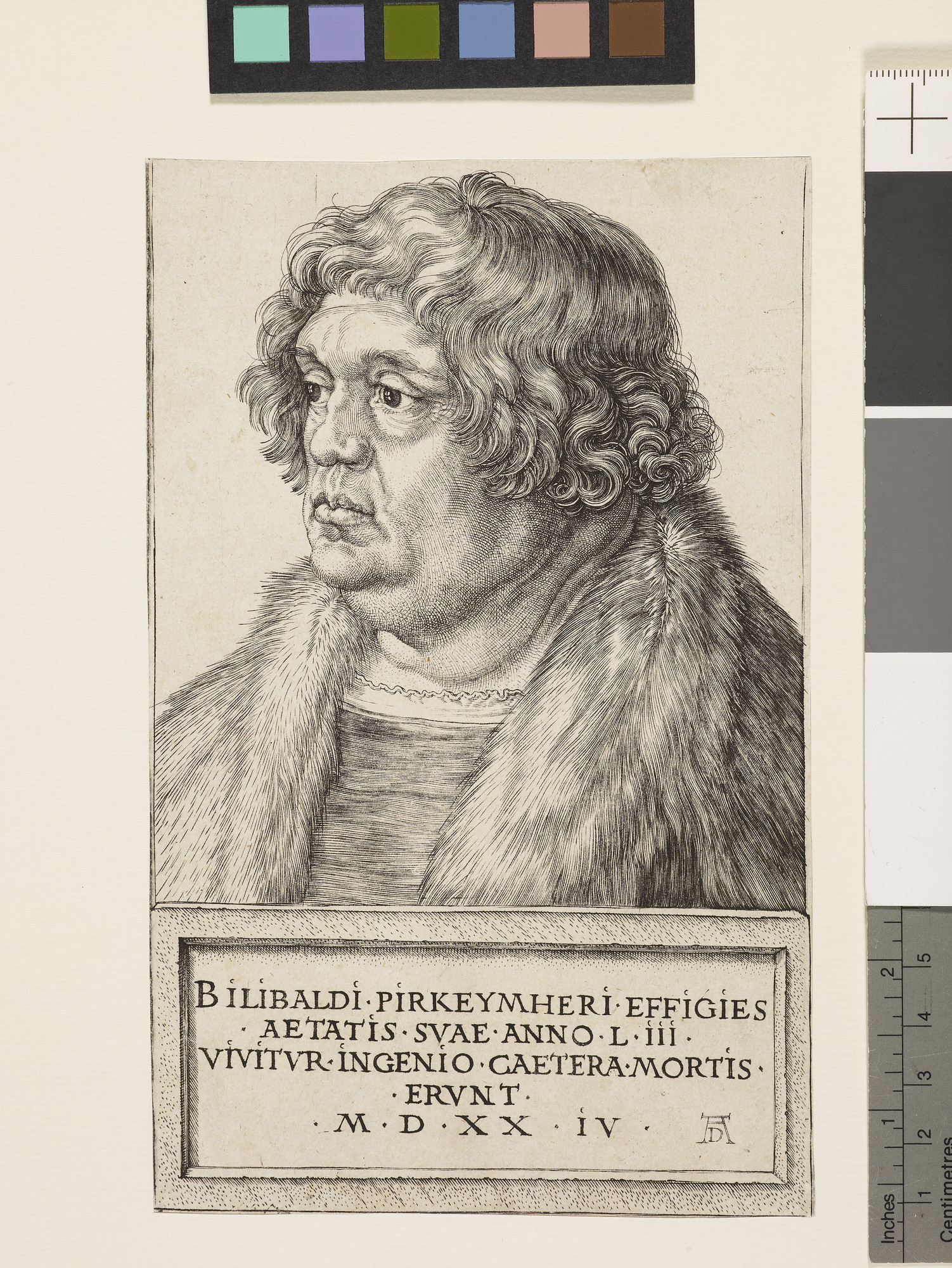

| Albrecht Dürer (1471 – 1528) was born on 21 May in Nuremberg, the “unrecognised capital” of the Holy Roman Empire of the German Nation and labelled “Augusta praetoria imperii” (principal city of the Empire) by humanists (Anzelewsky, 1982, p. 7). Dürer had many influential people in his life who would affect his creative mind and allow him to achieve the position of pre-eminent artist and court painter (Münch, 2005, pp.181-182). Noteworthy influences include Anton Koberger (important and influential printer in Nuremberg and goldsmith); the Pirckheimer family (enterprising merchants and inventive craftsmen – especially Willibald Pirckheimer who was influential in Dürer’s humanist connections); Michael Wolgemut and Wilhelm Pleydenwurff (patricians and Dürer’s teachers) (Eichler, 2007, pp.10-13).Dürer’s training in his father’s goldsmith workshop allowed him to visualise the sculptural qualities of objects and their spatial relationships (Panofsky, 1955, p. 4). This would have a profound effect on Dürer’s career as a painter and printmaker and his ability to create extraordinary quality in his intaglio works. Dürer would come to discover that, by ‘breaking the rules’ of intaglio technique, he would be able to strengthen the illusion of spatial depth, plastic modelling, textual concreteness, and even luminosity. One such method that Dürer discovered was to add refinements to the technique of ‘hatching’ and ‘simple cross- hatching’ to create the technique of double-cross hatching’ (Panofsky, 1955, p 66; Fuga, 2006, pp. 62-63). Evidence of this is contained throughout the print in question; including the display of movement in the horse, the sheen of the knight’s armour and the varying shades to represent the division between background and foreground. The image is still clear and bright and the definition of the shading via the cross-hatching technique allows you to notice the contrast between the characters amid a dark and foreboding setting.

Between 1512 and 1517 Dürer become actively involved with commissions for the Emperor Maximilian; including the largest woodcut made from 192 separate wood blocks – The Triumphal Arch. Dürer was kept quite busy with the Emperor’s requests, the years 1513 and 1514 allowed him time to work on his own projects to enable a continuing source of income from the sales of new editions of his woodcut series (Eichler, 2007, p. 88). An example of the latter work is this print, entitled The Knight, Death and the Devil. Dürer completed the piece in 1513 as evidenced by the date within the plaque that shows his recognisable AD monogram.

Panofsky claims that Dürer was probably aware of the fact that this print, together with two others (mentioned below), would be an important enterprise as was manifested in the special form of the signature (Panofsky, 1955, p. 151). The ‘S’ before the date is thought to stand for Salus, which is equivalent to Anno salutis (in the year of grace), a form of dating that Dürer frequently used in his writings (Strauss, 1973, p. 150). This can be seen in the identical placement of the date lines of his first drafts for the introduction to his Treatise on Human Proportions, composed between 1512 and 1513.

The print is probably part of a set depicting closely related ideals of virtue in medieval scholasticism: theology, intellect, and morality. This print (which Dürer simply called Der Reuter; or The Rider) embodies the state of moral virtue. Intellect and theology are represented in Dürer’s other prints of the same oeuvre entitled Melancholia I, and St. Jerome in his Study. These three copperplate engravings are thought of as Dürer’s greatest engravings and are referred to as his Meisterstiche (master engravings). This print was created first, while the other two followed in 1514. The three engravings are of a similar size and format, and they share an overall silvery tone with brilliant whites and blacks. The Meisterstiche represent Dürer’s supreme achievement as an engraver (Panofsky, 1955, pp. 151-153).

In this print, the rider is not distracted and is true to his mission. He rides on, looking neither left, nor right, nor behind him. Incidentally, the horse and rider are modelled on the tradition of heroic equestrian portraits with which Dürer was familiar from his time spent in Italy especially given his interest in Leonardo da Vinci’s drawings on proportion. One of the distractions to his moral path is symbolised by the Devil – with his ingratiating grin and pig nose. The Devil is portrayed as being powerless when ignored by the rider. The other distraction is symbolised by Death – who is a ghostly corpse without a nose or lips. Death holds up an hourglass to the Knight as a reminder that his time on earth is limited (Wolf, 2006, p. 47).

The Knight’s true destination or journey is represented by the castle in the top background – a safe stronghold that rises above the dark forest and symbolises God. The dog has long been a symbol of faith, while Eichler (2007, p. 91) regards the lizard as a representation of religious zeal. However, the dog could also represent this role. The whole scene represents the steady route of the faithful, through all of life’s injustices and temptations, to God.

Eichler and Strauss have suggested that Dürer based his depiction of the “Christian Knight” on an address from Erasmus of Rotterdam’s Handbook for the Christian Soldier (Enchiridion militis Christiani, circa 1502) (Eichler, 2007, p. 91; Strauss 1973, p. 150): “In order that you may not be deterred from the path of virtue because it seems rough and dreary…and because you must constantly fight three unfair enemies – the flesh, the devil, and the world – this third rule shall be proposed to you: all of those spooks and phantoms which come upon you as if you were in the very gorges of Hades must be deemed for naught after the example of Virgil’s Aeneas…Look not behind thee.” (Panofsky, 1969, p. 221)

Campbell Hutchinson suggests that another influence may have been that Hans Burgkmair’s chiaroscuro woodcut of 1508 that depicted the Emperor Maximilian as “the last knight”, in full armour and on horseback. His reputation as warrior and tournament hero, and his dedication to the militant St George, had inspired a number of knightly images in the imperial lands during this period (Campbell Hutchinson, 1990, p. 116).

Hotchkiss Price notes that Dürer fashioned his artistic endeavour in order to foster devotion in a quest for salvation. He writes that Dürer believed he was in the possession of a gift from God and that he needed to create devotional aids to assist with salvation (Hotchkiss Price, 2003, p. 280). Dürer’s Knight, Death and the Devil certainly fulfills this goal.

|

| LiteratureAnzelewsky, 1982

Fedja Anzelewsky, Dürer: His Art and Life, translated by Heide Grieve, London: The Gordon Fraser Gallery, 1982.

Eichler, 2007

Anja Eichler, Masters of German Art: Albrecht Dürer, Königswinter: Tandem Verlag, 2007.

Fuga, 2006

Antonella Fuga, Artists’ Techniques and Materials, Los Angeles: The J. Paul Getty Museum,

2006.

Hotchkiss Price, 2003

David Hotchkiss Price, Albrecht Dürer’s Renaissance: Humanism, Reformation, and the Art of Faith, Ann Arbor: The University of Michigan Press, 2003.

Hutchinson, 1990

Jane Campbell Hutchinson, Albrecht Dürer: A Biography, Princeton, New Jersey: Princeton

University Press, 1990.

Metropolitan Museum, 2000-

“Albrecht Dürer: Knight, Death, and the Devil (43.106.2)”. In Heilbrunn Timeline of Art

History. New York: The Metropolitan Museum of Art, 2000–.

http://www.metmuseum.org/toah/works-of-art/43.106.2 (27 September 2010)

Münch, 2005

Paul Münch, “Changing German perceptions of the historical role of Albrecht Dürer” in Dürer and his Culture, eds. Dagmar Eichberger and Charles Zika, Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2005.

Panofsky, 1955

Erwin Panofsky, The Life and Art of Albrecht Dürer, Princeton, New Jersey: Princeton

University Press, 1955.

Panofsky, 1969

Erwin Panofsky, “Erasmus and the Visual Arts.” Journal of the Warburg and Courtauld

Institutes, 32 (1969): 200-227.

Strauss, 1973

Walter L. Strauss (editor), The Complete Engravings, Etchings and Drypoints of Albrecht

Dürer. New York: Dover Publications, 1973.

Wolf, 2006

Norbert Wolf, Albrecht Dürer: The genius of the German Renaissance, Cologne: Taschen, 2006.

|

| Contributor Jeffrey Fox , University of Melbourne student enrolled in the subject Medieval Manuscripts and Early Print.Edited by Tim Ould, research assistant on this project and PhD candidate in Art History at the University of Melbourne. |

DÜRER'S MASTER ENGRAVINGS

There are no prints more highly regarded by art historians and appreciators alike than Albrecht Dürer’s master engravings. Having seen a quality print of Adam and Eve in person and taken a magnifying glass to every square inch, I can say that, objectively speaking, there is not a single line out of place anywhere on the print.

Albrecht Dürer. Adam and Eve. Engraving. 9 7/8 x 7 7/8”. 1504.

The engravings are a cycle of three images that encompass the stages of religious belief and doubt. Although similar in content and approach, Adam and Eve is generally not included in the list of the master engravings—probably because it was made nine years before Knight, Death, and Devil. In spite of that, I think it’s worth looking at as a preface to the cycle. It introduces many of the recurring symbols and sparks the religious debate.

Adam and Eve depicts the moment, before the Fall and the Expulsion, when the Devil encourages them to eat from the tree of knowledge. The scene is filled with animals living in harmony with each other as if the dynamic of predator and prey simply doesn’t exist. A cat sleeps next to a mouse, a hare lays behind the cat, a buck walks behind the Tree, a bull naps in the background, a parrot rests in a branch above Adam’s head, a mountain goat perches on the cliff in the far distance. The crowned serpent wraps around the tree and passes an apple to Eve.

In the following images, Dürer explores the dynamic of faith and knowledge within a context of the emerging humanism in the early 1500’s.

Albrecht Dürer. Knight, Death, and the Devil. Engraving. 9 9/16 x 7 3/8”. 1513.

As symbolic images go, Knight, Death, and the Devil is pretty simple—things mean pretty much exactly what you would expect. The Knight himself represents steadfast devotion and unquestioning faith. The dog (“Fido”) represents fidelity. The hourglass in Death’s hand represents the limited time of life. The horse, normally afraid, represents the overcoming of fear through training. In contrast, Death’s horse hangs its head, disinterested in all events. The skull represents death. The lizard is the Serpent transformed. Death is right there, reminding the Knight of his omnipresence. The Devil reaches up to scratch at or touch the Knight, ready to knock him off his path.

Melencolia I might be the most frequently debated and confusing image ever. Without written notes from Dürer himself, it’s taken a long time to figure the image out completely, but we can be pretty sure of what everything means.

Albrecht Dürer. Melencolia I. Engraving. 9 7/16 x 7 5/16”. 1514.

Just by glancing at the image, you can get a sense that this is about complete and devastating depression. The figure looks depressed, and “melancholy” is in the title. Without understanding the details, you can understand the mood, tone, and feeling of the image—everyone knows melancholy and what that entails.

The overarching structure of the print is the overlap of the spiritual world and the real world within a single image. As we run through the symbols, you’ll start to see which ones belong to which. Additionally, you’ll notice that the linear perspective is slightly off and uncomfortable in a few places, which is strange for Dürer given his absolute and total mastery of perspective (we’ll come back to that when we talk about the ladder).

The hourglass, this time hanging on the wall, still represents the larger passage of time (a lifetime). The dog, still loyal, sleeps at the figure’s feet, curled up in a ball as dogs do when they’re relaxed in their environment. The town, a castle high above the horizon in Knight, Death, and Devil, is now a coastal town below the horizon line, grounded in the real world. The bell, once around Death’s horse’s neck, hangs on the wall next to the hourglass with its pull-rope running out of the frame.

There are a few other objects that don’t have a huge amount of symbolic significance but cue you in to the action of the piece: creation. Running down the left edge and counterclockwise, you see a forge burning just behind the oddly shaped stone block, a hammer on the ground, a square in the corner, a planer, tongs peeking out from below the fabric just above the planer, a saw, a straight-edge, some nails, and the tip of a bellows just under the signature and date.

Next to the sphere is a censer, typically used in religious rituals. The title is written on the wings of a not exactly anatomically correct bat, a symbol of spiritual darkness. There is a balance hanging around the corner from the hourglass, symbolic of measurement in both a physical and a spiritual sense. The main figure has a ring of keys, symbolizing access to knowledge and power. The cherub sits on a grinding wheel and appears to be writing notes on a tablet. In the main figure’s hands, you see a compass, both for the measurement and creation of physical objects and symbolic of divine creation. Next to that, the hand rests on a book—the then-modern symbol of knowledge (instead of an apple).

The figure wears a wreath of some kind, and typically this would be symbolic of victory; however, they’ve been able to identify some of the leaves as belonging to plants associated with the treatment of melancholy.

On the wall, there is a 4 x 4 square with numbers in it, with any row or column or diagonal adding up to 34. This particular square has planetary associations with Saturn, melancholy, and the age of Christ at his death. This was supposed to be a metaphor for the discovery of the divine order within mathematics.

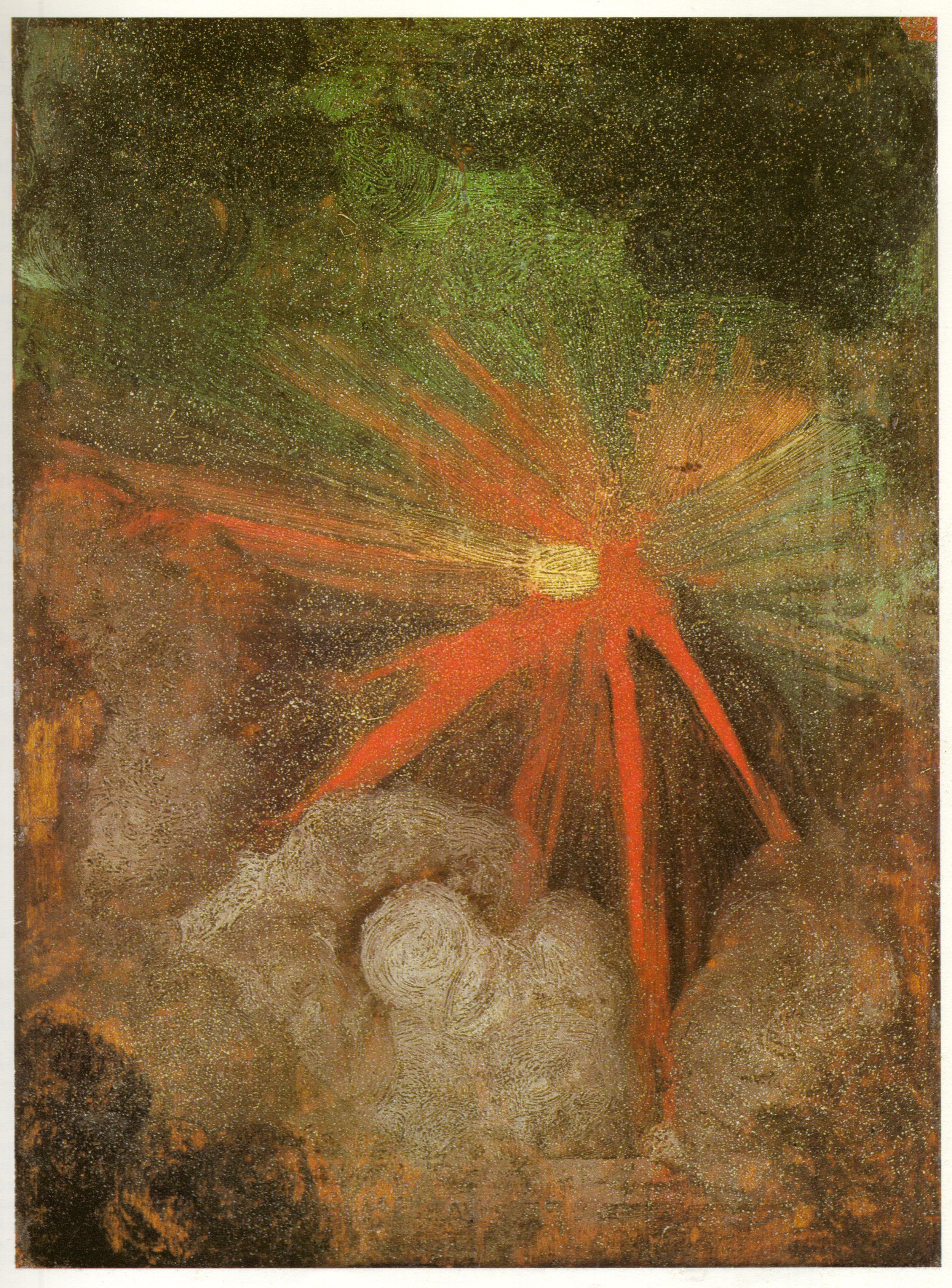

In the background, there is a rainbow, another symbol of the divine within the real world. The point at the end of the streaking rays is a comet—historians were able to figure that out when they found a painting of a comet on the back of another of Dürer’s other pieces. This also carries associations of heavenly bodies interacting with the mundane and real world.

Albrecht Dürer. Comet. Painted on the reverse of St. Jerome in the Wilderness. Oil on panel. 9.1 x 6.7”. 1495-96.

The ladder, with its associations with Jacob’s Ladder, runs from the ground up above the top edge of the print. The perspective of the ladder is a little bit off—it seems to run into and through the building it’s supposedly leaning on, and I think that means that it’s meant to be read in a symbolic sense rather than as a mere tool.

The cherub (a being traditionally of the 2nd highest order) itself is a symbol of a close connection with God. Here though, it’s brought down to a workshop on earth.

The winged figure (maybe an angel, maybe not) is typically seen as a female, but I think it’s fairly androgynous—in various depictions, angels wore basically the same thing whether male or female (robes). Regardless of gender, it’s a spiritual being now working in the physical world. The pose, with chin rested on hand, is one that Dürer used repeatedly through his career, and it’s an indicator of physical rest and spiritual unrest. The figure sits just at the moment when it’s stuck, frustrated, and unsure of how to progress.

This leaves the last 2 symbols and the ones that have caused a lot of trouble over the years. The sphere and the polyhedron. The sphere is pretty easy: a symbol of the divine perfection of God’s creation. It has no corners, one side, endless, perfect. The polyhedron is different, though. It’s not perfect. It has chips on the corners and doesn’t seem to be an ideal shape.

In this era, blocks of stone were quarried as rhomboids, meaning that their sides were parallel, but the angles weren’t 90 degrees like a cube or rectangular solid. If you were to imagine a rhomboid stood up on one point of one of its corners, the creature and it’s cherubic assistant have lopped off the top and bottom points to create this odd polyhedron.

Essentially, the creative plan here was to lop off planes from this rhomboid, getting smaller and smaller and more and more precise in order to create a replica of the sphere. When the figure and cherub realized that this was an impossible task, they stopped, and that leaves us with the moment of the image.

The metaphor—that attempting to create a circle from a square by drawing out tangent lines was impossible—came from Dürer’s association with Renaissance humanism. He was friends with Willibald Pirckheimer, who introduced him to these types of ideas. This one in particular comes from Nicholas of Cusa, who wrote and illustrated the idea in a previous publication.

Albrecht Dürer. Willibald Pirckheimer. Engraving. 1524.

The sphere and block is a three dimensional translation: God’s perfection can only be approximated by man. And that’s the central creative dilemma—try to create the perfect art work, and no matter what, it’s not possible. This print emphasizes the frustration, angst, and spiritual doubt at the center of that thought.

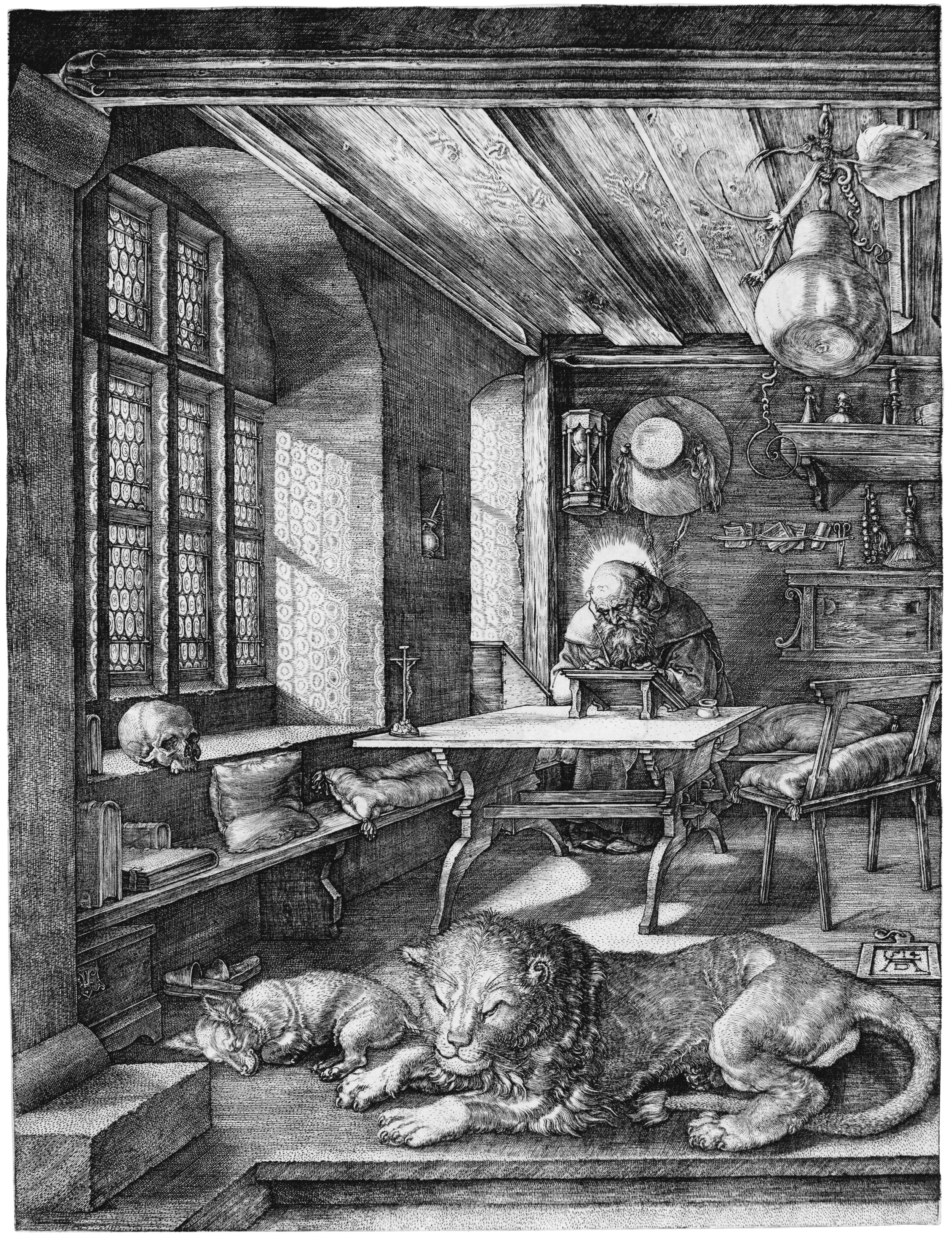

In contrast, St. Jerome in His Study shows a man who has come to terms with the facts of his own imperfection, has reconciled his faith, and works comfortably in his study. You still see the presence of death—the hourglass, the skull, and so on. There is a lion this time, an attribute of St. Jerome, and another dog sleeping peacefully.

Albrecht Dürer. St. Jerome in His Study. Engraving. 9 11/16 x 7 7/16”. 1514.

The biggest difference is the light. There’s a halo as well as light spilling in from the window as if it’s God’s light illuminating the room. There is a gourd hanging in the foreground, representing spiritual growth and development.

The feeling of peace with St. Jerome is one that can only come after a period of religious doubt—he’s aware that faith is a choice, that perfection is impossible, that spiritual perfection can’t come from imitation or approximation or anything humans can do on earth.

Taken together, these images sum up the varieties and stages of religious experience in a way that’s still completely real and completely truthful. I think that Melencolia I is under scrutiny so much because it creates a kind of tension that we still find relevant. We’re in a humanistic world again, caught between faith in technology and faith in the old gods. With images like Knight, Death, and Devil and St. Jerome in His Study, there’s less to talk about because everything has a resolution. I don’t think we find as much relevance there at this point in our society’s cultural development. We like chaos, we like debate, and we thrive on tension.