Baroque: Guide to the Age of Opulence

1 February 2018

What was the Baroque?

The Baroque was a period of art history that dominated the 17th and 18th Centuries.

It was preceded by, and to some extent, overlapped with the classically derived Renaissance style and the expressionist Mannerist style, and was succeeded by Neoclassicism.

However, whilst the Renaissance and Mannerist styles dominated painting and sculpture, the Baroque was an all-encompassing extravaganza, influencing all of the arts including painting, sculpture, architecture, music, ballet and theatre.

Through drama and excess, it sought to inspire an absolute and total sense of awe into the senses of the viewer. It was designed to swallow mere mortals up in its magnificence: a spectacle of extravagant artefacts in extravagant surroundings.

The Baroque was a movement that exhibited tremendous themes as monumental spectacles: intense light, grand visions, ecstasies and death, religious conversions, martyrdom, and a commitment to religious commemoration.

Whilst many of its overarching themes were initially religious, after some time the Baroque became a style in its own right and came to connote a movement in the arts that was synonymous with power, wealth, grandeur, majesty and ornate excess.

Where does the word Baroque come from?

There are several theories as to how the word Baroque came into use.

The most widely accepted theory is that the word Baroque derives from the Portuguese ‘barroco’, which was a word used by jewellers to describe irregularly shaped pearls.

The pearl can therefore be used as a metaphor to distinguish between the preceding Renaissance style and the Baroque itself.

In pearl terms, the classically influenced Renaissance would be perfectly formed, circular and gently glowing. By contrast, the Baroque pearl would be bulbous and exuberant, hard to handle and exciting in its irregularity.

Where, when and why did the Baroque originate?

In the early 16th Century, the Protestant Reformation swept through Europe. This left the Catholic Church in crisis, as the new, Protestant brand of Christianity splintered Europe, converting many individuals and even nations to its cause.

In reaction to the threat, the Catholic Council of Trent was formed. Between 1545 and 1563 they devised a plan to gain back ultimate political and religious power: the Counter-Reformation.

The plan was dependent on the wealthy Catholic Church as the leading patrons of art and architecture in the 16th and 17th centuries. The Council of Trent calculated to use these mediums as propaganda to restore Catholicism as the central European religion.

They decreed that all creative mediums and visual arts must communicate themes of faith and religion in the most excessive, majestic and impressive manner possible. They wanted the Catholic faith to awe and visually shock the public, who were mostly illiterate, in ways that had never been seen before to secure their support.

What was created in accordance with the Counter-Reformation became known as the Baroque style, which used Catholic wealth and authority to inspire steadfast religious devotion and spirituality.

The Baroque became a glittering visual and cultural means to underline the Catholic Church, autocratic regency and the upper classes, linking monarchies with religion and upholding the faith.

When and where did the Baroque take place?

The Baroque was conceived as the Counter-Reformation in Trento, where the Council of Trent had met between 1545 and 1563. When their plan for the Counter-Reformation was put into action, it blossomed from the very heart of the Catholic Church in Rome.

By 1600 it had taken a strong hold as the predominant decorative style of art and architecture in the city.

It soon spread further through Italy and to Spain and then throughout Europe, initially to the Catholic nations. In every place the Baroque touched, the movement gained momentum, breadth and diversity as it adopted the local customs within it.

Even countries where the Protestant Reformation had taken hold, such as England and much of Northern Europe, adopted and adapted the Baroque style to suit their means.

In time, the Baroque became the very first truly global movement, spreading intercontinentally to South America through Catholicism, and to Asia and the Far East through trade and exchange.

After 150 years, by 1750, the Baroque was widely accepted to have evolved into the Late Baroque, which is often referred to as the Rococo style. By the 1780’s, the true end of the Baroque was signalled by the growing taste for rational and proportionate Neoclassicism.

What was the Baroque influence on Painting?

Baroque painting is characterised by religious themes and a naturalistic, realistic appearance. Paintings were most often of people: faces, bodies, stories and portraits.

The figures were depicted in action, theatrically and dramatically. No composition was restrained – the immediacy of every movement was conveyed on canvas as bodies overlap and tumble together, playing leading roles in their painted theatre.

Figures were often taken from the Bible or mythology, conveying messages and stories to inspire and engage the viewer emotionally and spiritually.

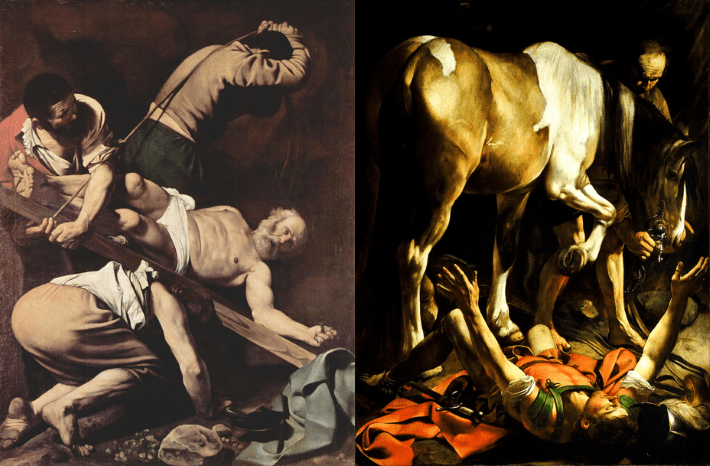

Michelangelo Merisi da Caravaggio (1571-1610), more often referred to as just Caravaggio, is considered one of the finest creators of the Baroque style of painting in Italy.

He developed the unique technique of chiaroscuro – the juxtaposition of glowing light and intense dark in painting – which afforded his paintings warmth and dramatic naturalism. Chiaroscuro became synonymous with Baroque painting.

Paintings in the Baroque style by Caravaggio and other artists were often used to decorate Catholic churches as altarpieces or in chapels, and they were often framed architecturally, within marble pillars and heavy ornamentation.

The Crucifixion of St. Peter, 1600, Caravaggio (left) compared to The Conversion on the way to Damascus, 1601, Caravaggio (right)

The Spanish painter Diego Velazquez (1599-1660) was exceptionally influenced by his travels in Italy, and some of the characteristics of the Italian Baroque that were made popular by Caravaggio can be seen in Velazquez’s works.

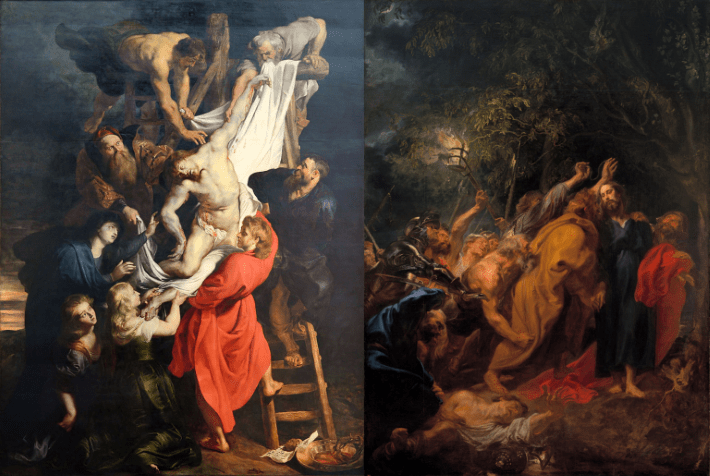

In Northern Europe, the Flemish painter Peter Paul Rubens (1577-1640), became widely known for his paintings in the Baroque style that were distinctively colourful and sensuous. He most often painted grand and emotive compositions of Christian and classical history.

Rubens was the teacher of Anthony van Dyck, a Flemish painter who is often credited with taking the Baroque style of painting to England. There, he was employed as court painter to King Charles I and executed many aristocratic portraits as well as mythological and religious subjects.

The Descent from the Cross, 1612-14, Rubens (left) and The Betrayal of Christ, 1620, Van Dyck (right)

What was the Baroque influence on architecture?

Baroque architecture was characterised first and foremost by its vast and monumental size. It was designed to envelope a person inside it and force the viewer to surrender to its magnificence.

St. Peter’s Square and Basilica, Rome could fit the Statue of Liberty under the dome, and has a total capacity three times that of Wembley Stadium! © Francois Malan via Wikimedia Commons

It would be hard to mention Baroque architecture without the two lions of Italian art – who were often described as rivals – Francesco Borromini (1599-1667) and Gian Lorenzo Bernini (1598-1680).

Both were famous for the architectural mark they left on Rome in the multitude of Baroque churches, fountains and public squares they designed and built.

Baroque buildings can best be described as ‘architectural sculpture’. They feature many facets, leading the eye from one detailed ornamentation or vast room to the next in a sequence of grandeur.

Buildings were influenced by Classical proportions yet took shape on a much more ostentatious scale.

The facades of buildings were symmetrically ornamented with fluted and twisted columns, contrasting elements, domes and depths and protrusions to create light and shadows. Windows and doorways were decorated and framed as though they were a stage.

View of the altar of Sant’Agnese in Agone, Rome, c. 1652-72, showing tones of green marble and red marble as well as white Carrara marble © Lalupa via Wikimedia Commons

Each aspect of architectural proportion was magnified and intensified, resulting in giant porticos, monumental columns and broad, sweeping steps on the approach.

Not only were these buildings colossal from the outside, they contained entire other worlds within them – a heaven created by man on earth that was all around and even above.

Baroque churches, of which many were built, were always built with a dome and interior vaulted ceiling which was often painted with frescos of religious allegories.

The magnificent Baroque architecture of Rome would provide inspiration for stately homes and palaces across Europe, which were often monumental in scale and would contain a complex geometry of rooms within. The Baroque style of architecture in these residences would almost always be built on a symmetrical plan, spreading out from a central axis.

Without doubt the most famous palace built in the Baroque style is the Chateau of Versailles in France. The French Baroque style which was developed and established there came to characterise the reign of King Louis XIV.

The palace was built by several leading French architects, including Jules Hardouin-Mansart, and is of colossal proportions.

Rear view of the Chateau de Versailles, Paris, showing its monumental size, columns and vast colonnades © ToucanWings via Wikimedia Commons

The exterior and the interior of Versailles were conceived as one; Baroque architecture on such a monumental scale required an equally monumental interior design scheme.

Charles Le Brun (1619-1690) was famous for the decoration of one of the most famous rooms in the world – the Hall of Mirrors at the Chateau of Versailles, which is frescoed with allegorical scenes depicting King Louis XIV as a god, and commemorate his victories and glory as King.

The Hall of Mirrors, with frescos by Charles Le Brun © Myrabella via Wikimedia Commons

The Palace of Versailles exemplifies how the Baroque evolved away from its original motivation as a religious style and adapted to local customs. At Versailles, the Baroque served to uphold the majesty and importance of the French monarch, rather than that of the Catholic Church.

The French Baroque, with Versailles at its core, became a style in itself, which many other nations looked to and attempted to emulate.

For example The Russian Tsar, Peter The Great, was so impressed by the French Baroque, following visits to Paris and Versailles, that he took French architects back to Russia with him, where he set about building his new capital city of St. Petersburg.

The Peterhof Palace in St. Petersberg, which is often referred to as the 'Russian Versailles', was constructed by order of Peter the Great, and takes inspiration from French Baroque palaces built under the reign of Louis XIV © Andrew Shiva via Wikimedia Commons

What was the Baroque influence on the decorative arts and interiors?

Much like architecture, painting and sculpture, the Baroque style of furniture and interiors featured heavily ornate and grand decorations. What it lacked in religious content it made up for in glittering magnificence.

Interiors were an outward display of wealth, and individual pieces can be characterised by the presence of putti (small, cherubic figures), scrolling foliage, highly detailed marquetry and woodwork, rich and extravagant upholstery and a general heaviness to furniture and decorative pieces.

Intense, contrasting colours and gilding were prominent in furniture, and entire rooms were hung with tapestries or covered with ornate, textured wallpaper in symmetrical, extravagant patterns.

Rich mouldings and heavy finishes allowed details of light to shine against recesses, creating shadows and painterly effects similar to those in architecture and paintings.

State Bedchamber of the King Louis XIV, Chateau of Versailles © Jorge Lascar via Wikimedia Commons

What was the Baroque influence on sculpture?

Sculptures in the Baroque style were often commissioned by the church to bring religious scenes to life.

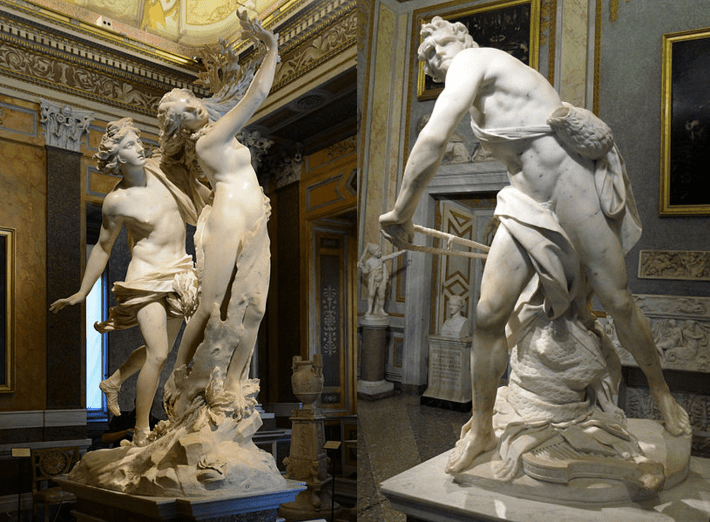

Mostly figural and allegorical, Baroque sculptures were influenced by Classical disciplines and proportions, yet characterised by their dynamism.

Works in stone were naturalistically rendered to show flesh tension with taut, rippling muscles and a sense of movement. Figures spiral around an invisible vortex or reach out into the space around them.

Sculptures for the outside would adorn fountains and piazza’s, and capture the energy of upward movement, causing the viewer to look up toward them.

Many sculptures which were made for interior spaces would be surrounded by stage-like architectural elements, such as flanking columns and pediments.

The Ecstasy of St. Theresa, 1652, Bernini © Livioandronico2013 via Wikimedia Commons

Gian Lorenzo Bernini, who had been so well celebrated as an architect, was even more prominent as a sculptor and is widely accepted as the leading sculptor of the Baroque. His most famous work is the Ecstasy of St. Theresa, 1652, which adorns the church Santa Maria della Vittoria, Rome.

In the Ecstasy of St. Theresa and other works, Bernini was celebrated for rendering sculpted figural groups with ‘flesh’ that appeared to behave like living skin – dimpled or bulging – as the sculptural figures interact with one another.

Apollo and Daphne, 1622-25, Bernini (left, © Alvesgaspar via Wikimedia Commons) and David, 1623-24, Bernini (right, © Sailko via Wikimedia Commons)

Dramatic facial expressions, clenched fists and outstretched fingertips were applied in combination to convey the urgency, excitement or importance of a sculpted scene, brought to life in marble and stone.

How are we influenced by the Baroque today?

Even in the modern and contemporary world the impact of the Baroque still reverberates.

Many richly decorated homes incorporate the drama of the Baroque into their design scheme today - it is not necessary to understand the Baroque to feel its grandeur.

Furthermore, the extensive Baroque movement saw the development of many artistic qualities and techniques that have been adapted and used ever since.

One of these is the use of illusion in art, most often referred to as ‘trompe l’oeil’ (to trick the eye), which was famously used by the architect Borromini in the Palazzo Spada in Rome, where he did not have the space to adhere to the colossal proportions of the Baroque.

To deal with this, he simply made things look bigger than they were, by creating a forced perspective of diminishing columns and a floor that gradually sloped upwards.

The forced perspective arcade at the Palazzo Spada, c. 1632 by Borromini. © Livioandronico2013 via Wikimedia Commons

The Baroque influence can be felt by anyone showing a reverence for the history of art, architecture and design.

Rome, the catalyst at the very heart of the Baroque movement, receives over 4.2 million tourists each year, who flock to see the city’s rich and extensive Baroque art and architecture.

In France the impressive Chateau of Versailles alone greets more than 3 million visitors each year, eager to experience the glittering grandeur of the French Baroque.

The extensive conservation and careful preservation of the many precious built, painted and sculpted relics of the Baroque allows us to experience the power and the monumental grandeur of the movement today.

The widespread travels of the Baroque touched every corner of the earth, meaning that we are never too far away from the spectacles left to us by the age of opulence.